The Column of Lasting Insignificance: May 7, 2011

John Wilcock

Cuba Diary (part two)

Havana, April 2011

THURSDAY: Decided to skip this morning’s lecture in favor of the hotel’s pool, but when I arrived, the usual bunch of British teenagers had again not only monopolized all the loungers but had covered the tiled floor with the wet pages of their homework pinned down with sandals to dry. It seems that earlier, their work had dropped in the pool, into which, oddly enough, their owners rarely entered.

Later I caught up with Cliff, the director of our tour group, and asked him to summarize today’s lecture. Apparently, it had not been a very cheerful session. He said that after decades of social investment in education and research, Cuba had just about reached the point where it was about to make the shift from the typical Third World export profile (based on agricultural goods and minerals) toward a First World export profile (where high value-added professional services are the biggest foreign exchange earner) when along came the global economic downturn. That, along with the need for heavy food imports at rising prices and persistent low productivity domestically, exerted pressure for major economic reforms.

I remember reading that the government had decided it would be necessary to cut half a million workers from government employment (out of a population of 11 million) and obviously, it will take time for everybody to find new jobs. So far there has been a spate of pocket-sized restaurants opening and hair-dressing salons but obviously, that has not filled the gap.

Needing something more cheerful, I asked Cliff if he knew any Cuban jokes, and after the briefest of pauses he replied:

“Okay, well one day Fidel’s friends took him to a pet shop to buy him a pet and asked him what he’d like? Would be he interested in looking after a tortoise?

‘How long does a tortoise live?’ Fidel asked cautiously, and when told that, well maybe a hundred years, Fidel replied ‘Oh no, that wouldn’t do. I’d be heartbroken when he died.’”

After lunch, we set off for the Consejo Popular Pocito Palmar which turned out to be a joyous occasion. All of Havana’s neighborhoods include a community center like this one where local people can get their questions answered and help with their problems. My mother used to volunteer for one in postwar England, called the Citizens Advice Bureau, and today there’s a telephone equivalent in many cities, including New York.

In Havana, such casas have the added element of housing a trova which is a form of music and more or less a stage or setting for same, invariably in these circumstances non-professional, and involving pretty much everyone who wants to sing, dance, or play an instrument. It was refreshing to attend this impromptu concert of unpretentious — some quite talented — amateurs, and before long everybody was crowding the miniscule floor and joining the dance. My friend Stephen Mansfield claims that Cuba can be defined by the sounds of its ubiquitous rhythms which he says run deeper even than politics. “For as long as there is music to listen to,” he wrote, “Cubans, even in times of hardship, have never stopped dancing. And in Cuba, there is always music.”

FRIDAY: The tap water is unreliable because the US embargo has blocked access to a cheap and efficient filtration system, so everybody buys ($1) bottled water. It’s available everywhere and clutching our bottles we board the bus for a 10-hour excursion to Vinales, northwest of Havana.

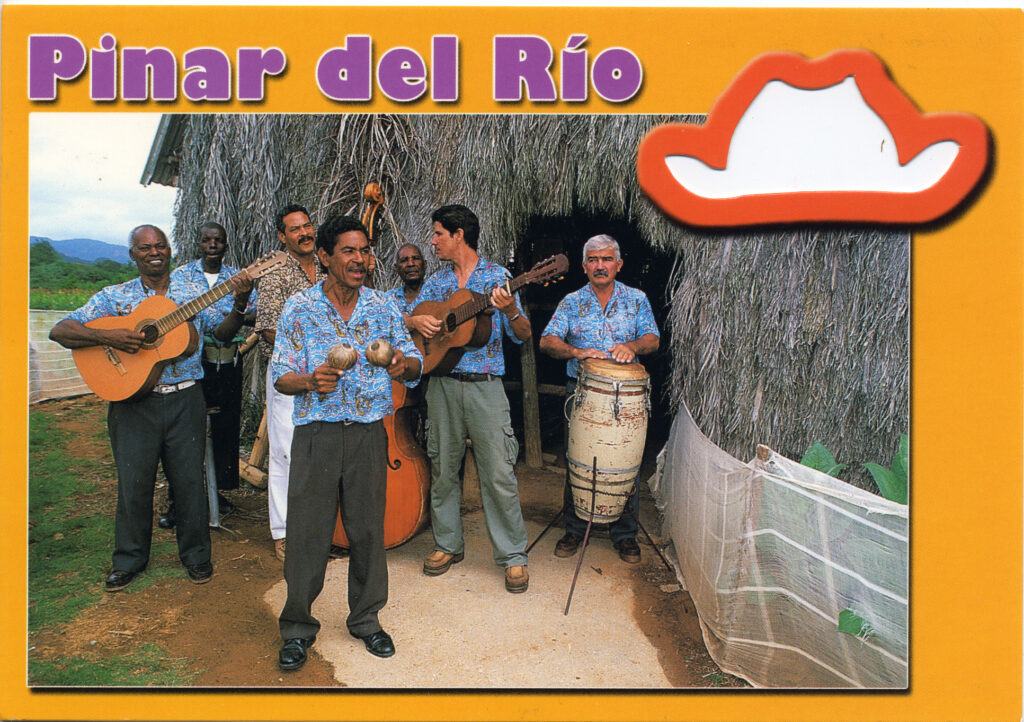

I hadn’t expected too much, but it proved to be an eventful day, beginning with two stops in Pinar del Rio to watch rows of workers deftly assemble cigars (a good worker can roll about 100 per day) and then to a nearby distillery where rum is bottled and flavored with guava beans.

A brief stop to watch a man grinding sugar cane, and sample a glass of the sweet juice, reminded me that sugar had for centuries been Cuba’s biggest industry, once employing half a million workers, and producing half the world’s supplies. (A role now supplied by Brazil and India.) After the Revolution, most of the sugar went to Russia in return for billions of dollars worth of oil, but when Soviet subsidies dried up the industry collapsed disastrously and had to be downsized by two-thirds.

Some of the old sugar mills have been converted into tourist museums, the fields devoted to other crops. Ironically, much of the industry could have been converted to ethanol production to supply US demand were it not for America’s refusal to have any dealing with its little neighbor (and the greed of US corn producers who wastefully produce ethanol with much less efficiency).

The tour continued with our entry into a rugged cave, dodging the rugged stalactites that threatened our heads, eventually boarding a boat to finish the dimly-lit underground journey, emerging near a restaurant for an a la carte lunch.

This is tobacco country. The dark, crinkly leaves can be admired hanging on racks in every barn and soon we make a stop to meet Benito. But first, a diversion to inspect a huge and garish mural, which Castro’s government commissioned. This “history wall,” replete with dinosaurs, covers hundreds of square feet of a cliff and ostensibly represents the region in prehistoric times, based on ancient artifacts supposedly discovered by the first Spanish invaders who visited the area.

The gaudy mural is a bit vulgar actually, but is sort of hidden in a backwater, offers an excuse for setting up a rest stop and bar, and in no way intrudes on the rest of what is generally acknowledged to be Cuba’s loveliest valley.

Onwards to rendezvous we meet Benito, a broad-shouldered handsome fellow with a rancher’s hat and Clark Gable-type mustache who looks every inch like a tobacco farmer or coffee plantation owner. He rolls a cigar with the adroit skill of somebody who’s practiced for years, exchanging flirty smiles with the pretty guide whose arm gestures while translating seem practiced. We finish the afternoon in Benito’s house, served coffee by female members of his family in the kitchen while some of the men whipped out their cigars and joined him in the other room.

SATURDAY: A morning tour of Old Havana, filled with impressive old buildings lining narrow cobbled streets. A section of the original water ditch, zanja (like the one in early Los Angeles), is marked off near the grand National Museum whose displays include the original contract between the US and Cuba over Guantanamo. (The Chocolate Museum turns out to be a confectioner’s shop.) On a stall, three small dachshunds wearing sunglasses are carefully guarded from cameras by an imaginative entrepreneur who demands pesos to get closer, and women dressed as Carmen Miranda circulate carrying baskets of wax fruit. Picking up a copy of the weekly English edition of Granma (named after the yacht which carried Fidel Castro and his group of 82 revolutionaries from Mexico) I was surprised to find it as turgid and difficult to read as it was half a century ago when U.S. “underground” papers were all on the complimentary mailing list.

“The necessity of generating alternatives capable of alleviating the burden faced by the state in maintaining the finances of all regional areas has prompted the leadership….”

is how one story begins and you’ll surely agree that if you want people to pay attention that is not the most eye-catching way to do it.

It’s a short tour and I returned to the Vedado, to spend the afternoon swimming in the pool and finally finding the time to read a treatise by a South Carolina sociology professor Charles McKelvey which explained Cuba’s political system. This eschews professional politicians and begins at a very basic level with delegates chosen by local groups of constituents “who know them personally based on their character, reputation, and ability to represent them.” Contrary to most foreign belief, only 15% of adults are members of the Communist party which has considerable moral authority but does not make laws or elect the president, a task carried out by the National Assembly.

“It is ironic,” writes McKelvey, “that while many in the West assume that Cuba is less protective of political rights, in fact, they are developing a system that is deliberately designed to ensure that the right of the people to vote is not manipulated in a process controlled by the wealthy.”

Nobody is allowed to “buy” elections and, in fact, the newspapers are owned not by private individuals or corporations but various organizations representing such as farmers, students, workers, and the Communist party itself. “This is a restriction on the right of property ownership, a restriction imposed for the common good, in particular, to ensure that the people have a voice and that the wealthy do not have a voice disproportionate to their numbers.”

Three blocks west of the Vedado is the classy Hotel Nacional de Cuba (doubles begin at $170) which retains all the grandeur of the luxury hotels of old, but with a magnificent coffee shop which offers both old movies and cheap prices: salads and soups $4, hamburgers $5, steak and fries $8.

Frank Sinatra used to hold court here, along with his mobster friends such as Lucky Luciano and Meyer Lansky, and their favorite movie star George Raft. Today, of course, it’s respectable as can be and a charming place to sit on the terrace overlooking the sea while sipping a frozen daiquiri ($4)

Among the taxis outside the Nacional — and virtually any car can be a taxi — is a superlatively restored 1959 Cadillac convertible, huge and shiny, with ostentatious tailfins, a popular hire for nostalgic joyrides. My favorites though are the tiny, orange, two-seater bubble cars that feel like you’re breezing along in a half-opened clam shell.

|

|

|

SUNDAY: The journey to Santa Clara (pop: 237,000) took about three hours. Almost in the center of the country, it is famous, among other things, for being the site of the final battle of the revolution in late 1958. Che Guevara led one of two guerrilla columns that attacked the city, (the other was led by Camilo Cienfuegos) and they successfully upended a train full of troops and supplies sent by Batista. He was so unnerved by the subsequent battle for the town that he fled Cuba two days later.

The site where the train was derailed is marked with a couple of old railroad cars and the bulldozer that did the trick, and a few hundred yards away is a massive monument to Guevara, whose remains and those of some of his colleagues are preserved in the adjoining mausoleum. Che was murdered in Bolivia and his ashes belatedly brought home.

The pleasant town is centered around the Parque Vidal in which sits a statue of Maria Abreu de Estevez, wife of Cuba’s 1902 vice president Luis, and a major benefactress among whose gifts was a theater on the square whose proceeds were devoted to helping poor children.

Long ago, the park observed the familiar Latin American custom — still seen in smaller towns of Mexico — of being a mating/meeting ground for young adults who would walk around and around the park in counter circles checking each other out. Doubtless, such courtship continues today in subtler fashion, and certainly, the park is usually crowded, women with their children, roller skaters, stilt walkers, and often competing musicians with their instruments, or more likely boom boxes.

Back at the Vedado, I continued to resist my normal urge to watch the news. Without English-language papers in Cuba, I’m totally ignorant of what’s going on in the world and amazingly I feel the better for it, even to the extent of eschewing television (available in the room are CNN, BBC News, A&E, HBO, and lots of soccer). If this is what it takes to break my time-wasting habit, it’s been an added bonus.