The Column of Lasting Insignificance: January 18, 2014

by John Wilcock

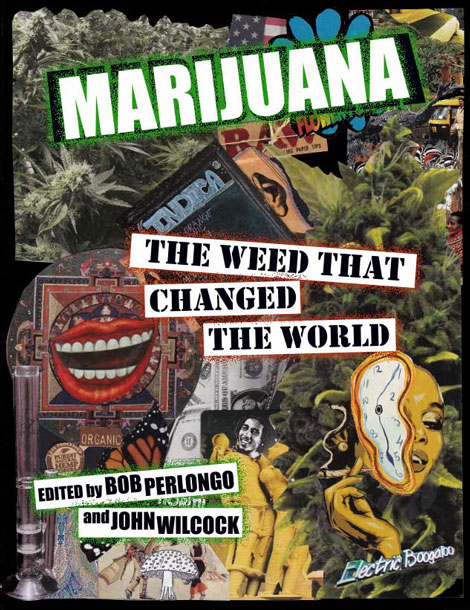

HERE’S ANOTHER IDEA that will never come to fruition. It’s based on my feeling that what the world is ready for is a weekly comic aimed at literate adults. That means no Batman or Spiderman or any of those other boring mythical figures who filled the thoughtless lives of so many teenage Americans. And certainly ixnay to the trivial, vacuous strips that pollute the Sunday papers. The popularity of graphic books and the ever-shorter attention span of the average reader has convinced me that there’s a publishing niche waiting to be filled — a zeitgeisty newsmagazine covering the social/cultural/political scene entirely visually. The criteria would be simple: anything whose graphics would be at least 50% of the total content. (My short-lived tabloid Collage lasted only three issues in the 1960s. The world wasn’t ready for it then, but it may be now. Even in these cyber-crazed times, artwork is more satisfying in print than read from a screen).

Unfortunately, none of the potential publishers to whom I have pitched the idea of Chaos Comix agree with me. Too far out, they say; too expensive; a risky gamble.

My formula would be the same as I imposed on the East Village Other whose editorship I took over at Walter Bowart’s invitation in 1967:

Pot, art, religion, politics, sex, sociology, revolution, and humor (sometimes these overlap). Politics would be fronted by Tom Tomorrow or some similar political strip and there would also be a running commentary on the doings of Congress. DC-t Street or DC.t Beat would be working titles, and there would be a regular report on the comix’ own candidate campaigning for president.

For more than a century, Italians have been familiar with Fumetti, narratives combining photographs and drawn graphics and text balloons and there’s much to be learned from Japan’s manga comics.

The two major tent poles, continued each week in Chaos Comix would be:

- Comic strip biography of some contemporary gadfly

[an example might be the current biography of me currently in progress on Boing Boing by Ethan Persoff & Scott Marshall] - An adventure story with independent but related episodes

[an example would be Claude Pelletiere’s Plain Clothes Nuns whose

habits disguise their unceasing DEA quest for mary jane malingerers.]

Some feature ideas:

This isn’t art!

(bad guesses by famous critics considered retrospectively)

Fake Book Jackets

(How to Cheat on your income tax; Lincoln, the man and the car; Pregnancy, its cause and cure; Funerals can be fun;)

Perverted brand names

(a la Jay Leno’s feature);

Ordinary people with star’s names;

Playing with the $ dollar bill (Dick Gregory and other versions); Shakespeare on Golf;

History of Chap Books;

Constructing, making, doing things, step by step (see Phil Niblock’s movies or any issue of Popular Mechanics);

Where’s Waldo?

Parody Burma Shave Signs

the devil’s dictionary

Julius-Haldeman’s little blue books

the witches almanac

dance by dummies

Travel: Brief travel capsules illustrated by the currency or stamps of the particular country (ancient currency, pre-Euro especially)

Art: Artist of the week

Real and fake paintings side by side

Reviews: All reviews of books, films, whatever, presented in graphic panel form — an improvement on those boring stills currently duplicated in every paper.

Classics: reviews of long-established books by the likes of Milton Glaser, Steve Heller, all the best graphic artists

Miscellaneous: The ranks of comic strip artists are huge, varied, and very wide, with many of the best practitioners of the Sixties and Seventies still at work. Nevertheless, as a variation from the pure ‘strip’ form itself, all kinds of graphics belong and will enhance this comic. Such items include the following: posters, postcards, Tarot cards, playing cards, visiting cards, dominoes, signs, wine labels, foreign candy wrappers.

Chaos Comix.

UNDERGROUND CARTOONISTS were always ahead of the times and behind in their rent. Twenty five bucks was pretty much all they got in the ‘60s for their often prophetic work with distribution limited to scattered head shops, themselves always under threat of being busted. For most artists, the underground papers were their sole outlets, although eventually a small group of top cartoonists—Art Spiegelman, Bill Griffith, S. Clay Wilson, Robert Crumb, Gilbert Shelton, among others—gained access to a limited mainstream audience.

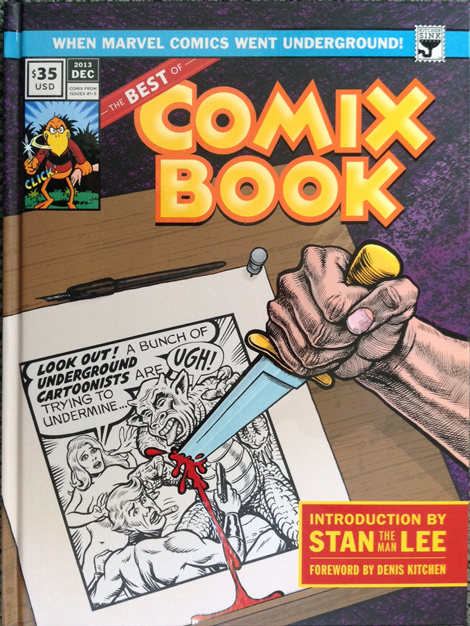

But there were dozens of others, some doing brilliant if somewhat esoteric work, and few held much hope of ever breaking through. The comics industry was dominated by such giant corporations as Marvel and Scotland’s D.C. Thompson Co. whose ample finances and wide distribution appeared to give them a stranglehold. And maybe best-known to all was Stan Lee, a New Yorker who began at Marvel as an inkwell filler and proof reader before becoming a cartoonist himself. With his collaborators Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko he eventually introduced the world to Spider Man, the Hulk, Fantastic Four, Iron Man, Thor, the X-Men and dozens of other fictitious heroes. In 1973 he was appointed Marvel’s publisher and made a dramatic decision.

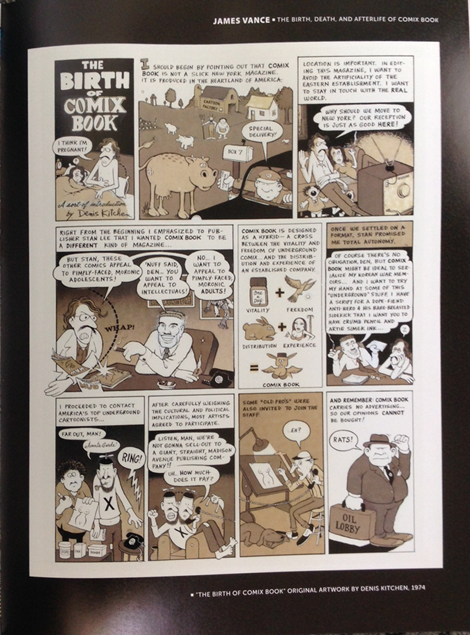

“One of the most courageous things I’ve ever done — editorially that is — started when my friend Denis Kitchen and I decided that the great comic book company I worked for should publish an underground comic book to fully round out its line,” writes Lee, in reference to Comix Book, the result of their joint project. “Now, you’ve gotta understand what a daring concept that was. During my entire career I had written comics to be read and enjoyed by readers of all ages, comics that parents could read with their kids if they so desired. But now, with the advent of Comix Book, we were seeking to enter a new market — the underground market, where anything and everything goes.”

The collaboration did not go entirely smoothly. “Things don’t always work out the way they’re planned,” Lee said. Reluctant at first, Kitchen was subsequently accused of selling out, especially by some of the already successful cartoonists. Then later Marvel tried to renege on a precedent-breaking agreement under which they had agreed to return original drawings to the cartoonists themselves.

On the other hand, most of the young previously-unknown cartoonists were overjoyed to actually receive decent payments for their work, coupled with a hugely-increased print run of 200,000 and wide distribution. And ironically, Marvel’s long-exploited staff cartoonists found that their complaints about what they saw as privileged treatment for the newcomers (notably the return of rights to their work) improved their own situation in future.

“After a year and five issues produced (three actually published by Marvel) Stan pulled the plug,” writes Kitchen, “officially for sales reasons, but also, I was told, to slam shut the Pandora’s box of precedents. Stan was a gentleman and sport throughout the entire process and Marvel effectively saved my company, Kitchen Comics, while keeping a good number of long-haired cartoonists better fed.”

The collection of the five issues produced 40 years ago has just been published under the subtitle When Marvel Comics Went Underground.

Comix Book

it’s here…