Exploring the Old West

by John Wilcock

U.S. ROUTE 395, a major north-to-south California highway that sometimes seems like a back road, is often depicted as a true reminder of the Olde West. Abandoned gold and silver mines, nostalgic ghost towns, and the rugged hills where hundreds of old-time movie stars made some of the earliest two-reelers are all part of a trip that crosses the stunningly beautiful High Sierras. West of the highway are Yosemite and Lake Tahoe, to the east, a trio of national forests and Death Valley.

Beginning just south of Victorville, site of a long-time air force base, and for its first 40 or 50 miles, US 395 heads mostly through featureless desert, the Mojave.

Just west of Kramer Junction, where it’s crossed by SR 58, is Boron whose Twenty Mule Team Museum presents the fascinating story of the borax (used for soap, glassware, china, ceramics, tile) mined in Death Valley which was transported for 162 miles to Boron. Before the arrival of the railroad, 26 carefully selected mules pulled 25 tons of borax and a tank wagon of 1,200 gallons of water, the team covering 16 miles per day and camping each night in the desert.

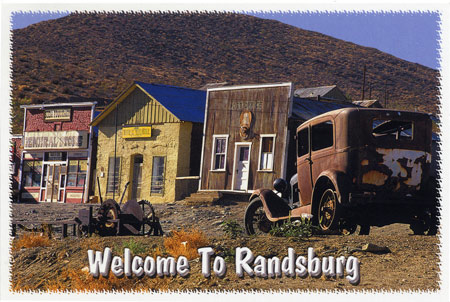

A more direct approach to US 395, especially from the west coast, is to head up CA. Route 14 through Boron to where the highway joins 395 at a trio of ghost towns: Randsburg, Johannesburg, and Red Mountain, all named like the adjoining Rand Mountains, after a similar gold mining region in South Africa, from whence some of the early miners came.

Randsburg (pop: 86) is the most interesting, with its charmingly relaxed Cottage Hotel which pretty much invites you to help yourself to what’s in the refrigerator after settling in to one of the spotless, comfortable rooms. Robin, the friendly owner, red hair cascading down her back, pops up occasionally to see if everything’s okay, but most contact is made via a phone in the lobby.

Two or three antique stores, a bar called The Joint, and a general store with a century-old soda fountain occupy most of Main Street, the most conspicuous examples of what once were hundreds of structures when the town’s population topped 8,000. Gold, first discovered here in 1895, was still being mined until WW2 by which time millions of dollars had been taken out of the Yellow Aster Mine. In 1912, the mine was paying $3 a day for underground workers, $2.50 per day for above ground.

Lacking restaurants, visitors head for Ridgecrest, about a dozen miles north, from which State Route 178 heads eastwards into Death Valley.

Back on Rte14, half a mile away, is one of the state’s finest microbreweries, Indian Wells (named after the valley you’re passing through). Try the Mojave Red, whenever you come across it—it’s delicious.

You might pass Pearsonville without noticing the huge warehouse and high wall which hides the sight of hundreds, perhaps thousands, of vintage cars. This is Pearsonville, population 17, two of whom are Lucy Pearson — known as “the hubcap queen” — and her mother Janice who initially assembled a collection of 80,000 hubcaps. For a decade it has been the place to come for replacement parts for old cars. There’s even a book about it: Pearsonville, CA 93527 ($18.88 on Amazon)

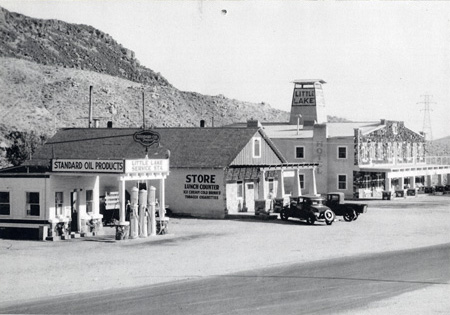

Coso Junction, an infinitesimal point on the map, is the focal point for seismic activity going back centuries — conspiracy thinkers allege that the Feds deliberately cause “test” earthquakes around here — but it’s not earthquakes that have removed the former communities of Dunmovin and Little Lake from the map, but the passing of time. As you can see from the picture below, the latter was once a regular stop along the highway. There’s no trace of the little community today.

At Olancha, SR 190 branches off to the east offering another way into Death Valley via Panamint Springs. The road skirts what would be the shore of the now-mostly barren Owens Lake, once 30 feet deep but whose waters were pillaged starting in 1913 by Los Angeles for its water supply. Although once covering 100 square miles, the lake is largely a salt flat today, although various lawsuits have restored some of the water and it is still a major stopover for thousands of migrating birds: snowy plovers, ducks, and geese. At the far side of the lake, another ghost town, Cerro Gordo, experienced a silver boom beginning in the 1860s which eventually totaled $17million. Thousands of pounds of the precious metal were shipped cross the lake on tiny steamers every day. Among its sites today are the sets of Star Trek V, originally filmed west of Lone Pine.

DEATH VALLEY, the largest of the National Parks at 3.3 million acres, hosts more than a million visitors each year, and sometimes literally goes years without any rain, with months in which temperature tops 120 degrees day after day. The Valley also has its ghost towns, the best known being Rhyolite near Beatty in the eastern Bullfrog Hills. “The desert seems bleak to the unknowing and the unseeing,” wrote Genny Schumacher in Deepest Valley. “(But) it has silence and order and space. It teems with life if you know how to look for it.”

Just before Lone Pine, where SR 136 leads to Death Valley is the Visitor Center where you can get information about, and permits for, the trail to Mount Whitney which sees 20,000 hikers each year, their numbers limited by the Forest Service which strives to protect the environment. It’s a 21-mile round trip which jocks can do in a day but the inexperienced might find easier to interrupt with an overnight camp.

Magnificent views of Mount Whitney, at 14,997 feet the highest in the lower 48, dominate the scenery for miles but is a particularly vivid site from here. Because of its distance, it actually appears smaller than the more prominent Lone Pine Peak (12,121 ft). Two near-photographic murals adorn the side of the Whitney Portal Hotel in Lone Pine, the creation of a local forest ranger, Dave Kirk, who patrols the hills in winter and works from a tiny studio in the Old Hotel Building downtown.

“I’m inspired by landscapes,” he says. “That’s why I was drawn here in the first place. For me to understand the essence of something I have to get my hands dirty. I can better interpret the landscape if I’ve touched it.”

Filming in the rock-strewn Alabama Hills, on the slopes of Mount Whitney, dates back to 1920 when it was the site of Fatty Arbuckle’s first full-length feature, The Round Up. That same year Will Rogers arrived to star in Water, Water Everywhere (1920), a tale about a group of ladies from the temperance society who manage to get a saloon closed down. Hundreds of movies involving well-known and unknown cowboy stars have been shot here.

The town was closely involved, reports David Holland in his seminal book On Location in Lone Pine. Bank robberies were filmed at the actual bank, locals and their horses hired as cowboy extras ($5 a day, more than doubled at the onset of the Actors’ Guild), and local rancher Russ Spainhower on call full-time as the ‘go-to’ guy for the Hollywood studios. Hopalong Cassidy (William Boyd), who starred in 66 movies between 1935 and 1948, was the first to use Spainhower’s ranch in Range War and Law of the Pampas (1939). What is now the Lone Pine Campground was the site for Tom Mix in Riders of the Purple Sage (1925) in moviedom’s early days.

The 42-room Dow Hotel (built in 1923) and adjoining Dow Villa Motel (on the site of a former church) has hosted countless producers, directors, and stars including John Wayne, William Boyd, Roy Rogers, Gene Autry, Stewart Granger, Errol Flynn, and Robert Mitchum, but the town took the succession of celebrities in its stride. “The only time I ever saw people go crazy over some star,” one local told Holland, co-founder of the annual Film Festival (who died in 2005), “was when June Allyson and Dick Powell stopped off at the Mt. Whitney Café for some tuna sandwiches.”

Enthusiasm by Kerry Powell and her husband for all this exciting action caused them to fill their Frontier Hotel with old pictures and posters, and this led to the first Lone Pine Film Festival in 1990 at which Roy Rogers dedicated a historical plaque. The 22nd annual festival is scheduled this year for October 8-10.

A reconstructed watch tower marks the site of the old Manzanar camp, one of a dozen to which Japanese-Americans were relocated on (unjustified) suspicion two months after Pearl Harbor in 1942. Altogether 120,000 were imprisoned and the story of this desolate place is re-enacted in a film screened at the restored high school auditorium. Every April many former prisoners attend Pilgrimage, a reunion of survivors.

Despite its size (pop: 669), Independence is the Inyo County seat with its majestic courthouse and century-old Commander’s House, a fine example of rural Victorian architecture. The tiny town is almost at the center of the Owens Valley, actually the deepest in America with the Sierra Nevada range to the west and the Inyo Mountains beyond the Owens River to the east.

Twenty miles further north at Big Pine, anglers head for the mountain creeks to camp and fish for rainbow trout, while in town, Carroll Thomas, celebrated as the country’s oldest living artist, welcomes visitors to his eponymously-named gallery where he celebrated his 101st birthday a few months ago.

YOU CAN STILL camp and swim at Keogh Hot Springs, founded in the 1920s as a health and leisure resort or you can save your soaking for Whitmore Hot Springs, a bigger place further north. Meanwhile, there’s Bishop (pop: 3,780), which likes to call itself the mule capital of the world due to its Memorial Day celebrations when hundreds of mules are roped, ridden, and admired, accompanied by country music and the usual fairground attractions.

Founded in 1861 by Samuel Bishop as a place from which to supply the huge input of miners, as far away as Bodie, northeast of Mono Lake, it is now a mecca for fishermen. In town don’t miss the extensive murals which decorate Bishop’s back streets: even the police station is decorated with a scene of the Old West in which the sheriff stands guard.

If you take US 6 from just east of Bishop you’ll eventually end up 3,205 miles away in Provincetown, MA.

Tom’s Place, at the foot of Red Slate Mountain (13,000ft), is a restaurant, bar, and general store whose cabins have been welcoming visitors since the early days of motoring. Just before, US 395 scales the Sherwin Summit at 7,000 ft, the first of five Sierra Nevada mountain passes traversed by the highway. After skirting Crowley Lake, a reservoir for the Los Angeles aqueduct, and the turnoff for the ski and fishing area of Mammoth Lakes, another climb culminates in Deadman Summit (8,036 ft), named for the decapitated body of a murder victim found here almost 150 years ago.

Lee Vining (pop: 222) is very much of a tourist town because Yosemite is less than two hours drive away via the 9,000-ft Tioga Pass on SR 120, but also for the proximity of Mono Lake with its widely-seen pictures of tufa towers sticking up out of the water.

These are created by a build-up of calcium carbonate formed from the salty waters combining with freshwater underground springs. All is explained in the unusually interesting lakeside visitor center which displays a film showing the millions of birds that use the lake as a stopover and mini aquariums holding examples of the pinhead-sized shrimp on which they thrive.

After cresting the Conway Summit ( which at 8138 ft, is the highest point on a California highway) but before reaching Bridgeport, where the antique-filled Bodie Victorian Hotel is doubtless the oldest in the state is the highway to Bodie itself, SR 270, closed in winter.

This most famous ghost town once had 10,000 population and almost 20,000 buildings of which 200 remain, some looking as though they were abandoned yesterday, especially stores with their still-stocked shelves. Only park rangers live there today and access is via an unpaved, 13-mile road on which you’ll usually find yourself for long stretches trapped behind a truck going 25mph.

The southern entrance to Lake Tahoe begins 20 miles north where SR 89 heads west over the mountains with endless switchbacks and dramatic views. US 395 continues north for hundreds more miles, cutting briefly through Nevada and eventually into Oregon.