The Column of Lasting Insignificance: June 29, 2013

by John Wilcock

Bakewell Diary

SATURDAY: Leaving my rented cottage overlooking town, I walk down a steep hill to The Rutland Arms, built in 1804 when it was a stop for the horse-drawn coaches that carried most of the traffic of that era. It’s an unshakeable local legend that Jane Austen stayed here while working on Pride and Prejudice. Print the legend, although it may not be true. Charles Dickens was certainly here, as well as Lord Byron, the author and critic Samuel Taylor Coleridge, the landscape painter JMW Turner, the poet William Wordsworth, and other notables of the day; some of the four-poster rooms (£159-£189) bear their names.

Beside a traffic roundabout at the main entrance, it’s the town’s major landmark — and it has WiFi! Opening my Kindle, beside a pint of Boddington’s, I check my email. The Rutland is by far the largest hotel in town and competes with the 19th-century Town Hall to host weddings. And that Jane Austen once stayed here is a tale repeated everywhere, too iconic to relinquish, although the town’s semi-historian, Trevor Brighton, says there is no evidence for the claim. This year being the bicentennial of Pride and Prejudice, Austen’s name is frequently evoked. “Does every single article mentioning Jane Austen have to begin with that ‘truth universally acknowledged’ bit?” asked Rose Wild in the Times last week. “Yes, I fear so.”

A rival for attention is the famous Bakewell Pudding which was said to have been made accidentally in the hotel kitchen in 1854 when an assistant to Alice Greaves, the cook, failed to blend the ingredients correctly, resulting in a unique product now known around the world. It is claimed by at least two other establishments around town, which have a “secret recipe” under lock and key. The trouble with this legend is that similar puddings were known at least 20 years earlier in other regions and a similar concoction is said to feature in the famous 1755 Dictionary by Dr. Samuel Johnson.

The market town of Bakewell (pop: 3,979), is a delightful place already well documented by the 11th century in the Domesday Book, when its church was esteemed enough to sustain two priests. Replete with 16th- to 18th-century buildings matched in style by those of recent eras, the town is just small enough to walk around, perhaps spending an hour designing and baking your own jug at a craft studio or dropping by Sarah Ridgeway’s art gallery, which occupies what was once the ostler’s cottage for the shabby White Horse Inn. This preceded the Rutland Arms and burned down in the late 18th century. The grubby town of those days, its dirty rundown streets muddy from straying sheep and cattle, nevertheless spawned many millionaires, one noble lord said to be making £300 a week at a time when a gentleman could live well on £700 a year. Few, of course, fared so well, it being a time when lack of money, poor food, and wretched living all contributed to early deaths; laborers sometimes at 21, even the gentry at 49, and less than one-third of the local population was over 34. Clothes gave people away: penniless workmen, for example, were likely to have but one set of clothes which their wives would wash and repair while they went to bed. But better times were coming: in 1888, one Bakewell hostelry boasted that visitors had a bathroom at their disposal and a decade later the town had 25 lodging houses.

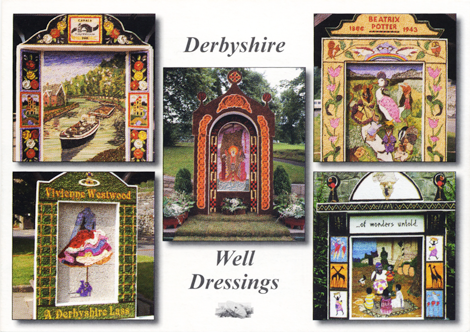

SUNDAY: By bus to Ashford in the Water, to see the newly decorated (defunct) water wells. Well dressing ceremonies throughout Derbyshire, prompted by the wells drying up a century ago, probably echo the Celtic custom of flower displays celebrating earth worship. The Romans established shrines at some water sources and there is a display of Roman votive offerings in Buxton Museum.

Flowers are collected from local gardens, and the petals, along with seeds, twigs, bark, maize, wood, berries, coal, coffee beans, are pressed into a paper design on water-soaked clay boards, then mounted over the dried-up wells. Boards are soaked in the river for a week, with the clay added riverside on a night when everybody comes to help. The petals and other decorative ingredients are pricked onto the boards (the paper pattern then carefully removed) with a cocktail stick or a horseshoe nail. Religious scenes, anniversaries, even — this year — a celebration of the Disney Channel with a rinky-dink depiction of Mickey Mouse. Other wells are devoted to Martin Luther King, Sheepwash Bridge, the TV timelord Dr. Who, and the gardener, Joseph Paxton, who reinvigorated the Chatsworth House estate. Inside Holy Trinity Church are similar floral depictions of old-time village scenes: candle-making, the blacksmith shoeing horses, work at the ancient corn mill. One of the wells adjoins the ancient Sheepwash Bridge where an annual ceremony took place yesterday. Baby lambs were penned, 80 at a time, at one side, while their mothers are pushed into the opposite side of the River Wye. Collared and leashed while wading to their offspring, their fleeces were cleaned with wooden paddles, the wool then sheared and sold. The bridge has low sides, the overhanging panniers of old-time packhorse ‘trains’ containing malt from Derby, along with salt, wool and cheese.

It was still not noon, and with the 17th century Bull’s Head a one-time coaching inn with oak beams and open fireplaces yet to open, I sat in the Women’s Institute and had a sandwich and a pot of tea. Then browsing a table laid with dozens of cakes and pastries. Although I regretted having missed the annual sheepwashing demo, I coincidentally found stories in two different newspapers about sheep. In one, a French college student in Shropshire was reported to have invented a battery-powered drone that could monitor a farmer’s far-flung sheep from the air. “There’s no substitute for a dog and a shepherd,” scoffed somebody, but as it happened, the other story dealt with exactly that — John Bell, 82, a retired Yorkshire farmer who had just set a world record by selling for almost $15,000 a sheepdog he had bought (for $500) as a 13-month-old puppy last year and subsequently trained. Bob, a border collie, has apparently gained an anonymous US owner. “He’s a natural,” mused Bell, “and I was expecting a lot of him.”

It was still not noon, and with the 17th century Bull’s Head a one-time coaching inn with oak beams and open fireplaces yet to open, I sat in the Women’s Institute and had a sandwich and a pot of tea. Then browsing a table laid with dozens of cakes and pastries. Although I regretted having missed the annual sheepwashing demo, I coincidentally found stories in two different newspapers about sheep. In one, a French college student in Shropshire was reported to have invented a battery-powered drone that could monitor a farmer’s far-flung sheep from the air. “There’s no substitute for a dog and a shepherd,” scoffed somebody, but as it happened, the other story dealt with exactly that — John Bell, 82, a retired Yorkshire farmer who had just set a world record by selling for almost $15,000 a sheepdog he had bought (for $500) as a 13-month-old puppy last year and subsequently trained. Bob, a border collie, has apparently gained an anonymous US owner. “He’s a natural,” mused Bell, “and I was expecting a lot of him.”

Back in town, I slipped on some greasy cobblestones and badly bruised my left thigh just before dropping by the Victorian Town Hall to request a few minutes with the newly re-elected mayor. Meeting in a nearby pub half an hour later, the boyish face of Paul Morgans was already familiar to me from a local paper’s picture of him — plastered with a custard pie. It was a voluntary PR sacrifice he’d made to publicize the forthcoming Bakewell Baking Festival. Pies and Prejudice is the slogan for this event, which a London performance art company called the Bureau of Silly Ideas (those Brits!) reveals is the centenary of the first custard pie scene on film. My video battery had run out so we agreed to a further mayoral meeting later in the week, and when I said that I had deliberately not rented a car for my visit, Paul said — wistfully it seemed — “I’ve never been in a relationship with anybody who had a car.” Solves the parking problem, I proffered. “In Bakewell,” he muttered, “we don’t have a parking problem; we have a walking problem.”

MONDAY: Just across from the giant Co-op supermarket, swans and ducks hang out beside the mini waterfall on the River Wye, celebrated for its trout fishing. It’s a pleasant walk alongside the river to the cricket ground, visiting the relatively new Thornbridge Brewery which quickly earned a national reputation and then a distribution deal with Sweden’s 400-strong chain of off-licenses. Crossing the bridge brings you to the sprawling Agricultural Center where hundreds of farmers come to buy and sell cattle and sheep. Accompanied by the nonstop prattle of the auctioneer, cows are led one by one into a tiny ring to be displayed, sold, and prodded out, all within seconds, as bewildered lambs are pushed from trucks into narrow pens. Veterinarian Giles Bramwell with his partner Willem Schaper are likely to have customers today. Operating from nearby Milford Farm for the past couple of years, they have treated many of the region’s animals. “Just as likely to be called out for an ailing llama as a lamb,” confesses Bramwell, “because the variety of farm animals has expanded. One minute I can be treating a poodle, the next I’m doing a cow cesarean. It’s never boring.” Encircling the Co-op, the Monday market in town takes place under a Royal Charter granted in 1330, and offers most of those wonderful things you could once find in the much-lamented Woolworths. It seemed time to visit the Original not-one-and-only Bakewell Pudding Shop where my information about being able to watch a pudding being made turned out to be untrue. I bought a small one anyway and would define it as a large, soggy tart made from puff pastry and smothered with a half-inch of strawberry jam. It was getting harder to walk, because of my bruised left thigh, so I put in a call to Pete, the hippie taxi driver, to meet me in Portland Square where I could amuse myself at The Wee Dram as I waited. This enticing booze bar, established by Adrian and Alison Murray back in 1998, stocks 600 different whisky varieties and soon brought Adrian an invitation to be a Keeper of the Quaich, an exclusive society founded by the leading Scotch whisky distillers. “Whisky has always been my drink of choice,” he enthuses, “it’s a mood drink so you need half a dozen to choose from.” The taxi collects me, zipping us past All Saints Church (15th-century font) and the Old House museum with its Tudor toilet, up the steep hill to my Rock Terrace cottage, where I make a belated start on the five morning papers that are delivered each day.

TUESDAY: Riding herd over a verdant 105-acre estate, Chatsworth House is England’s favorite country mansion, its 30 rooms with gloriously painted ceilings offering an art tour of the ages. The successive halls are lined with priceless paintings, which seem to occupy almost every inch of the often dimly lit walls, but here and there one stands out. Thomas Gainsborough’s painting of Georgiana Spencer, who, when only 17 had married William Cavendish, the fifth Duke of Devonshire. Thenceforth, until her death in 1806, Georgiana was known as the “Empress of High Society.” She was as famous and notorious in her day, as her descendant Lady Diana Spencer was more than two centuries later. “When she appeared,” wrote the French diplomat Louis Dutens, “every eye was turned toward her; when absent she was the subject of universal conversation.” When Gainsborough’s 1785 portrait — which depicted her wearing a wide-brimmed hat, with large sash and drooping feathers — was exhibited, dozens of wealthy ladies asked their milliners to whip up copycat displays for themselves. There are endless, timeless, wild rumors of Georgia’s sexual and financial extravagance to be explored. It’s a subject that demands further research.

Impressive as they are, Chatsworth’s art and architecture are far outdone by profit-seeking business savvy. Admission to the house and garden (£19) is just the start; for the true fan there are opportunities to attend behind-the-scenes lectures with the gardeners, the housekeeper, the duke and duchess themselves; visit the textile and floral departments; spend instructional days on keeping pigs or chickens; learn about the role in history beer has played before sampling some at the estate’s brewery. All these adventures have their price, and the company engenders considerable income from a vast array of gourmet items from its cafes and the enticingly mouth-watering Farm Shop. There are rental houses on the estate and a quartet of hotels (three called the Devonshire Arms) in nearby villages. There’s also a plenitude of free things: a maze, a farmyard filled with friendly goats, lambs, ponies, guinea pigs.

Chatsworth’s regular events include outdoor concerts, theatrical performances, art and culture exhibitions, and the annual Country Fair which presents horse shows, vintage cars, hot air balloons, pipe bands, falconry, parachute displays, acrobatics, musical events, gundog teams, archery with crossbows, sheepdog trials. Surely needs an app, whatever that is. And — we’re not through yet — the Annual Food and Drink fair (60 stalls) has ice cream sold from tricycles, medieval drinks brewed from plants, cheeses, cured meats, homemade pies, and products from the superstar Chatsworth Farm Shop. Oddly, despite millions of visitors, there is no direct bus from Bakewell and the change of buses is irregular and inconvenient. Returning from Chatsworth I was obliged to wait for an hour in the middle of nowhere until the connecting bus back to Bakewell appeared. I watched a trio of yellow-jacketed council workers trundle up a huge mower to chop down the grass verges, a mere three inches high and sprinkled with pretty wildflowers, infinitely more attractive than the resulting stubble. What a waste of money, I thought, only to be confronted later in the day with an editorial in the Independent ‘Let Our Verges Run Wild’, confirming my point. “If (road verges) were a national park,” I read, “they would be rightly valued as a wildflower preserve.”

WEDNESDAY: Rain in England is predictably unsurprising and the weather this spring is widely acknowledged to have been the worst for years, and now the very day that I’d decided to stay home and rest my bruised body, it did choose to rain, and gazing over the valley I saw a rainbow. In a recent newspaper essay, I had just read about one. “A rainbow doesn’t actually exist so it doesn’t really have an end where you can find a pot of gold. Optically speaking, it is just a distorted virtual image of the sun with each raindrop acting as a tiny imperfect mirror”. It seems that right from ancient times there have always been arguments about how many colors comprised the glorious spectacle, but at the time of my schooldays everybody was taught Real Old Yokels Gulp Beer In Volume which translates into Red Orange Yellow Green Blue Indigo Violet, the seven colors of the spectrum. Of course, each color merges imperceptibly into the next one, leaving no hard boundaries, and the rainbow itself can’t be seen unless the sun is low in the sky. In fact, the higher up you are, the more perfect is the half circle, and if you’re skydiving (they say) you might see the whole circle. “The way I see it,” wisely noted Dolly Parton, if you want a rainbow, you gotta put up with the rain.” My email to Steve Caddy, admiring his new magazine Bakewell Pure, had the rewarding effect of bringing him and his colleague up for a visit. The glossy mag is a more-than-usually-interesting guide to local events and made me wish I could still be here later this month, just about when you’ll be reading this, when 28 international dance groups (Appalachian, Armenian, Argentinian, for a start) will give free concerts and instruct £2 one-day dance workshops.

THURSDAY: A dozen little sidewalk cafes line some of the less trafficked alleys and cul de sacs of Bakewell, which happily is mostly bereft of chain stores. Huge supermarkets are “ripping the heart out of communities,” in the words of Derbyshire Times editor James Mitchinson who asked his readers to protest such “ruthless profiteers” as Tesco, which he accused of bulldozing pubs to build more superstores. A reader complained that there were already 42 Tesco stores within a 15-mile radius of the paper’s offices in Chesterfield.

A vast network of hiking trails spreads over this region of Derbyshire, the site of England’s first national park, whose Peak District authority publishes impressively detailed guides. On joining a metalled track at a gate, turn right, after 30 metres cross a low stile and take the path to the left, to the left, again keeping the river to the right… reads a tiny portion of the instructions for walking to Haddon Hall, a famously beautiful manor that was already old when the Manners family took up residence there in 1567.

Later abandoned for centuries except for a caretaker, the ancient house (a building has stood on the site since Norman Times) stately Haddon Hall has attracted numerous TV and movie productions, among them Jane Eyre (two films) and Pride and Prejudice (the Keira Knightley one). Lord Edward Manners, current scion of a family that has owned the house for 800 years, also owns the luxurious Peacock Hotel in the nearby village of Rowsley. Open weekends (April and October), daily (May–Sept.), admission £10. Special events include an Easter egg hunt, a Tudor cookery, a Tudor-style wedding with music from that era, folk nights, and concerts in the gardens.

FRIDAY: In the town library, adjoining the swimming pool, an entire shelf is devoted to biographies about Georgiana, the rip-roaring Duchess of Devonshire who inherited today’s equivalent of $70 million when her father died of alcoholism, and proceeded to piss most of it away on fashion, booze, jewelry, and gambling. Her preference was for faro, where players bet against the banker, a game adored by high society at the time. Georgiana charged dealers 50 guineas a night to set up tables in her house, gambled heavily herself, and at one point, after an $80,000 stock trading loss, was in debt to the equivalent of almost four million dollars. The Morning Herald and the Daily Advertiser featured her regularly, the latter enthusing somewhat unfathomably: “Her heart, notwithstanding her exalted situation, appears to be directed by the most liberal principles, and from the benevolence and gentleness which marks her conduct, the voice of compliment becomes the offering of gratitude.” In her award-winning bio in 1998, Amanda Foreman commented that “these fawning notices revealed more than just a weakness for party hostesses but made the paper eager to be associated with them.” Georgiana’s husband, the fifth duke who spent most of his time hunting, was not vastly pleased (she admitted she was frightened by him) but his disapproval was countered in 1782 when he met Lady Elizabeth Foster, who moved in as part of what observers called “a noble menage a trois.”

Mayor Paul dropped over with his journalist partner, Janet Reeder, and a bottle of wine. Paul had worked as a photographer for Hewlett Packard and Air Canada before coming to Bakewell ten years ago. “I love the fact that I have a place that other people want to visit,” he riffs, “because in the past, I’ve lived in places that nobody wanted to visit. Every day here feels like a holiday.” He’s been busy lately dealing with problems associated with what he claims will be the first festival in the world devoted to baking. At first, he couldn’t get insurance because the pie-throwing was classified as a sporting event, but after publicity, the company that insured last year’s London Olympics stepped up. “The world really would be a better place with less war and more custard pie fights,” he says whimsically.