The Column of Lasting Insignificance: March 30, 2013

by John Wilcock

Yangtze River Diary

SUNDAY: Considering how many infants were aboard the China Air flight from Los Angeles, they behaved surprisingly well, although like most single travelers, I dread being seated next to one. Maybe if all the families with young kids were obliged to sit together, mothers would quickly recognize how irksome other people’s children are — something they usually don’t know about their own.

The headphones program featured the (13-member) Twelve Girl Band who jazzily presented their version of Five Beats, from Brubeck’s Take Five. (Following up with a longer variation called Seven Beats. They were good.) After noting that China Daily, a government paper, includes the New York Times crossword puzzle and has Dilbert and Peanuts among its four comics, I turned my attention to the tabloid Global Times in which I read about what was to come.

The polluted air that had fogged-in Beijing so often recently, the paper reported, had caused huge sales of anti-fog masks. But it was as well to be aware, that not all masks were effective, especially the cotton ones embellished with cartoon figures. “Useless,” the paper remarked, “but in terms of keeping your nose warm, you can bet on it.” Two NYU students it’s said are selling a t-shirt whose colors changed in response to levels of pollution.

The polluted air that had fogged-in Beijing so often recently, the paper reported, had caused huge sales of anti-fog masks. But it was as well to be aware, that not all masks were effective, especially the cotton ones embellished with cartoon figures. “Useless,” the paper remarked, “but in terms of keeping your nose warm, you can bet on it.” Two NYU students it’s said are selling a t-shirt whose colors changed in response to levels of pollution.

Arriving at Beijing’s sprawling new airport required a long walk from the gate to a train which shuttles a mile or two to where the moving sidewalk (many) takes you to baggage claim. Bags, understandably, take a while to arrive. Beijing traffic is horrendous, with most miles of the ‘expressway to the airport,’ traffic-locked and vapor-enwrapped. The agreeably-relaxed Crowne Plaza offered a bed in a pleasant room with a half-moon washbasin and comfortable bed on which almost immediately I was asleep. I missed seeing the “pillow menu,” offering ten choices from a wheat cereal pillow to a bamboo charcoal pillow. You just had to ask.

Arriving at Beijing’s sprawling new airport required a long walk from the gate to a train which shuttles a mile or two to where the moving sidewalk (many) takes you to baggage claim. Bags, understandably, take a while to arrive. Beijing traffic is horrendous, with most miles of the ‘expressway to the airport,’ traffic-locked and vapor-enwrapped. The agreeably-relaxed Crowne Plaza offered a bed in a pleasant room with a half-moon washbasin and comfortable bed on which almost immediately I was asleep. I missed seeing the “pillow menu,” offering ten choices from a wheat cereal pillow to a bamboo charcoal pillow. You just had to ask.

MONDAY: Chongqing, (pop: 30million) where that party boss was arrested and his wife accused of murder, is where cruises down the Yangtze begin, and was the first inland commerce port opened to foreigners a century ago. It manufactures a million cars each year (Ford has three plants) and almost nine million motorcycles. During the 90-minute flight I read an uncomplimentary story about the behavior of Chinese tourists abroad who, wrote columnist Ding Gang, have not learned how to behave in foreign countries. After the success of a movie, Lost in Thailand, 26 charter flights deposited Chinese visitors in that country where — according to Bangkok’s Nation newspaper, their behavior ignored local laws and “violated Thailand’s customs and habits.”

Many of the visitors were accused of ignoring traffic laws by driving too fast on the wrong side of the street and against traffic on one-way streets. Chinese girls wearing shorts at Buddhist temples and couples renting rooms and then packing them with four or five people were other complaints. The columnist also deplored the Chinese habit of defacing architectural monuments with graffiti (Liang Qiqi traveled here). “Is this the Chinese way of warmly embracing the world?” he asked sarcastically.

Much of this, of course, can be attributed to how quickly the Chinese, a rural nation less than a decade ago, have vaulted into the 21st century and how much catching up they still have to do. On only a slightly smaller scale than the capital, Chongqing is stacked with huge new apartment blocks, row after row of them in every direction the eye can see. The billions that China’s central government has allocated to reducing poverty has lifted 25 million people in the past few years, shifting most of them from country folk into urbanites. Of course, it still has another 99 million to upgrade, prompting the World Bank’s Ulrich Schmitt to term the poverty reduction production program “highly successful (but) the remaining poor are harder to reach and more dispersed in remote and inaccessible areas.”

After a brief tour of Chongqing, during which I sat for awhile outside the downtown Starbucks and videotaped some of the myriad spiked heels pirouetting by, we headed for the ship. Soon I was ensconced in a comfy cabin, balcony overlooking the river and with refrigerator and CNN on the TV.

TUESDAY: Loudspeakers penetrate cabins with dual announcements at the ungodly hour of six. And continuously until breakfast ends at 8:15. All meals are served on the 2nd floor which means three flights of up and down stairs, thrice daily for those arthritic of us on the 5th. This floor does have the bar and lounge.

Still reading, I fortuitously opted out of today’s excursion to Fengdu, a group of abandoned temples atop a nearby mountain, described as “heavy walking excursion, with many stairs, points without handrails and inclines down.” What’s known as the “ghost city of Fengdu” was submerged by the miles-long reservoir of the Three Gorges Dam in 2003. The new city of Fengdu that replaced it was built high up across the river. This a.m. it could not be seen through the heavy mist.

Catching my attention was an amusing story about a woman pretending to be pregnant. This babe read that appearing pregnant would get you a seat on the crowded subway, so she bought a fake belly for 300yuan ($48) and surely found a seat. Then the plastic thing fell down to her knees and she to the floor, naturally to be scorned, ridiculed, and jeered by her fellow passengers. Her suit, saying that the makers had cheated her, was rejected by the Tongzhou Administration of Industry and Commerce on the grounds that sale of the item did not fall within “purchasing commodities or services for living needs.”

WEDNESDAY: Aboard the Victoria Sophia, our diversion downriver is into various gorges, water valleys joining the main river… Qutang Gorge… Wu Gorge… the Xiling Gorge 25 miles of towering granite cliffs topped with greenery… Longchang Gorge… Parrot Gorge. Transferring to a smaller boat brought us to the fabled Shennong Stream, a much narrower gorge named, like the mountain, after the legendary peasant who founded Chinese medicine while wandering these slopes in search of his magical herbs.

At the gorge’s entrance, everybody boarded peapods (long canoes) which, then tied to long bamboo ropes, were pulled through shallow waters from the hillside. Trackers is the name for these sturdy fellows with rope and harness, who run narrow paths carved into the slopes. In the old days when the peapods

carried fruit and vegetables to the market, the trackers worked naked. That was before the Three Gorges Dam opened up the gorge to tourism.

Less than a dozen Tujia families, all surnamed Yu, live in Tracker Village, as they have for generations. Many have never left. Most mornings, they row their sampans with oars and equipment downstream to handle the tourist-filled peapods. By afternoon they are back at their farms.

With three rowers upfront bending double up and down in harmony, and one at back handling the tiller, we head up the Shennong Stream, noting the ancient coffins suspended 100 feet above. Constructed from a type of wood that never rots, they have been hanging for centuries. Virtually inaccessible even to those who placed them there, they represent a desire to be as close to heaven as possible. In the hills here, once hidden among endangered plants, Hong fruit trees, and rare golden monkeys, were many ethnic tribes, living as they had for thousands of years. Building of the dam forced their resettlement into the new town of Badong. Unvisited, although we passed under the huge bridge, which replaced the centuries-old ferry across the river.

THURSDAY: At the bar in the lounge, a double espresso costs a hefty $6, but this is offset by free WiFi which enables me to check emails on my Kindle. Even though the Chinese authorities have been able to restrict admittance to certain critical components, they have proved to be progressive in access to the Internet itself. WiFi is free at the airport, for example, and also in Beijing’s numerous libraries. The city’s Municipal Bureau of Culture boasts that — in what it calls Digital Communities — anybody with a free library card can access 160 domestic newspapers, along with four million eBooks, two million ancient books, and millions of periodicals as well as 20,000 video lectures. “It’s quiet and the speed of the Internet is very fast. Now I will be here whenever I have spare time,” says Song Hui, a student who will graduate this year.

The tiny top-deck room in which a group always seem to be playing mah jong on a special table, also serves as a library where there’s a meager selection: well-thumbed paperbacks in a variety of languages. Not that I expected to find missing copies of the Tianlu Linlang. What’s that? A collection of ancient classics from the Confucius era which were scattered throughout China after 429 of them perished in an 18th century fire in the Forbidden City: 177 volumes are thought to remain, including Confucius’ Classics and Elucidations in Spring and Autumn Annals.

In January, the directors of Beijing’s Palace Museum and Taipei’s National Palace Museum agreed to a joint attempt to reunite the collection of the volumes, searching on both sides of the Straits where some are believed to be in private hands. “Study the past,” wrote Confucius (551–479BC), “if you would define the future.”

At the Sophia Cabaret in the lounge, many of the sweet-natured young employees donned fine robes of many colors and did dances and gestures onstage to warm appreciation.

FRIDAY: “I’m your dam guide,” he said to laughter, as our busload took off for a visit to the Three Gorges Dam, and an articulate guide he turned out to be. Under construction for almost two decades at a cost of $28 billion dollars, the Project we examine is the largest hydroelectric power conservancy project ever built, comprising 26 huge generators. To build it, more than a million folk spread over a million acres — thousands of tiny communities — had to be relocated. But the dam’s eventual completion ended centuries of floods along the Yangtze River which forever had brought devastation to millions. The dam itself, 600 feet high and almost one and a half miles long, turned 400 miles of the river into an immense reservoir stretching all the way back to Chongqing.

Here downriver, a palatial glass-and-concrete security building feeds us into the Three Gorges Project. Three successive escalators bring visitors up the hillside, past workers planting peach trees, to a wide plaza overlooking the docks and dam. Below us, explained the guide, the vast area over which the project sprawls, was once filled with mountains as high as those still visible across the river. All had been razed to create infrastructure for the Three Gorges Dam. From beside the fake fountain atop the hill, we view the locks, four boats wide, through which shipping passes, then down flower-bordered paths to the museum with its scale model where I had my first ice cream for a week.

The Yangtze River, the longest river in Asia (3,988 miles) is third-longest in the world, and in the area it covers from Tibet to Shanghai it produces more than one-third of the fresh water for one-third of China’s population. Before the Three Gorges Dam was built, huge floods were frequent, sometimes killing as many as 10,000 people at a time. The capacity of barge fleets heading up this stretch of river has been improved five-fold with commensurate financial benefits.

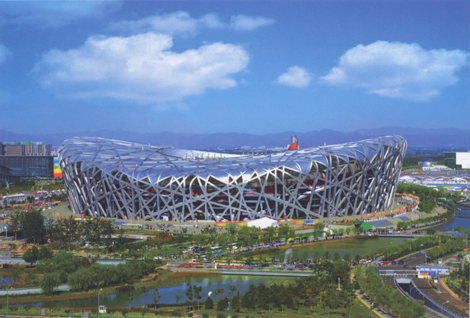

SATURDAY: Back in Beijing our young guide takes us for the inevitable trip to the Great Wall (it’s a two-hour drive), an interminable walk among hundreds of thousands through the seemingly endless courtyards of the Forbidden City and a close-up of the visionary National Stadium (Birds Nest) designed by the brilliant and globally-admired Chinese artist Ai WeiWei who is foolishly kept under tight guard by clueless Chinese authorities and not allowed to leave the country.

We took a night-time walk along the capital’s glittering Wangfujing Street, across from the hotel, which houses virtually every fashion name you’ve ever heard of and billboards by global vendors. A very narrow alley, lined with food stalls and jammed with bodies, is the popular night market. Armani’s glass building changes color, and Gap, Gucci, and Cartier stand out. That very day I had read that in January alone Chinese consumption of imported luxury goods topped $8.5bn — half of the entire world total. The report was by the Beijing-based World Luxury Association. Greed prevails, here as everywhere. Mark-ups have become excessive, causing unreasonable prices, and they should be curbed, declares Wang Zhifa, deputy chief of the National Tourist Administration. He has been urging price control officials to step in. [Interesting structure, hey?] Luxury items were 30% cheaper to buy overseas than in China, Wang reports, and a reduction in prices would result in more customers, both domestic and tourists. “A considerable number of luxury products that Chinese buy overseas are actually made in China,” he says.