The Column of Lasting Insignificance: October 13, 2012

by John Wilcock

Astoria, OR

THE LOCAL PAPER’S banner headline, Mary Louise Flavel found was big news in this Columbia River town where the Flavel family had been virtual royalty for more than a century, ever since Mary’s great grandfather, Captain George, sailed in and became the first local millionaire.

The Flavels always had a reputation for eccentricity, if not worse, culminating with the stabbing (and jail time for assault) by Mary’s brother Harry, who died in 2010 and remained unburied for months because his sister refused to pay for the funeral. She also, according to city officials, refused to pay property taxes on the 15th Street mansion in which she lived and abandoned when she left town and disappeared.

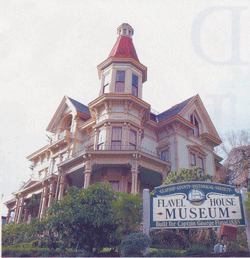

The city (pop: 10,000) put a lien on the fast-decaying property and searched the interior finding piles of century-old newspapers, unopened mail, ‘50s clothing, food in the refrigerator, and the body of a dead dog — a startling contrast overall with the grand Queen Anne style Flavel House Museum, four blocks away, which Captain George built in 1884 with its 14-foot ceilings, library, conservatory, and music room where his daughters, Nellie and Katie, performed.

|

|

High above the bay windows and pitched roof is a tower offering 360-degree views and from which the captain, an early bar pilot, could keep an eye on the tumultuous river. The house was gifted to the city long ago and welcomes 25,000 visitors each year.

The Daily Astorian was jubilant about tracking down the missing scion but had to promise not to reveal her whereabouts in return for an interview.

“Life in Astoria,” recalled Mary Louise, 87, “was great unless you were a Flavel,” adding sorrowfully that her family had been characterized and mistreated for generations, sometimes because of jealousy, other times because of cruelty. (Snobbishness may have played an early part: Captain George arrived in Astoria by sea, his wife Mary overland on the Oregon Trail, a route regarded as lower in the hierarchy.)

Mary Louise was indignant about the city’s intrusion into her now-derelict mansion, complaining what they had done was “completely illegal. It is my property. Their actions do not make it theirs.”

New Jersey-born Captain George made his fortune as an early river pilot. Some places acclaim firemen as their heroes, which is surely also the case here, too, but Columbia River pilots are on a staggeringly elevated level. Their training takes years, their licenses — authorizing them to handle everything from a

nuclear submarine to a 1,000-ft ocean liner — are granted only after proof of the kind of skills that make the average ship’s captain look like your everyday genius.

nuclear submarine to a 1,000-ft ocean liner — are granted only after proof of the kind of skills that make the average ship’s captain look like your everyday genius.

“These are mature pilots who risk their life on a daily basis,” says Astorian editor Patrick Webb. “Often they’re heroes to people who don’t know their names, have never met them but will turn out in grateful appreciation for the funeral of any of them.” There are about a score of pilots at any given time — a few are women — and many of them live out of town, visiting only for their specific assignment.

What’s the big deal? Well, picture where the expansive Columbia River smacks into the incoming Pacific Ocean, creating waves that can be 40 ft high. Add to that the frequent rain and dense fog, and imagine trying to guide an ocean liner “across the bar,” something that these death-defying pilots do every day of the year. The slightest misjudgment about the incoming or outgoing tides can be fatal, and has been on hundreds of occasions. Half a dozen times a year severe storms halt all operations. Not for nothing is the Columbia River Bar known as the graveyard of the Pacific.

Along the route of the colorful, waterfront trolley is the splendid Maritime Museum amplifying this watery saga in greater detail and, sitting outside, is a retired pilot boat, the Peacock, which crossed the bar 35,000 times during her 30-year career. The trolley, by the way, which parallels a narrow pedestrian boardwalk, runs the length of the town with many stops at riverside restaurants. It’s a bargain at one dollar for the 50-minute ride and for $100 per hour can be rented and packed with your friends (and presumably plenty of champagne).

Astoria celebrated its 200th anniversary last year having been founded by John Jacob Astor’s fur traders as the first permanent U.S. settlement west of the Rockies, six years after the arrival in November 1805 of that intrepid pair Meriwether Lewis and William Clark. “Great joy in camp we are in view of the Ocean, this great Pacific Ocean which we have been so long anxious to see,“ wrote Clark in his diary, “and the roreing or noise made by the waves brakeing on the rockey shores (as I suppose) may be heard distinctly.”

They had left St. Louis in May 1804, charged by President Thomas Jefferson with exploring the west.

“The object of your mission is to explore the Missouri river, & such principal stream of it, as, by its course & communication with the waters of the Pacific Ocean, whether the Columbia, Oregon, Colorado or and other river may offer the most direct & practicable water communication across this continent, for the purposes of commerce.”

“We were now about to penetrate a country at least two thousand miles in width, on which the foot of civilized man had never trod,” wrote Lewis. “The good or evil it had in store for us was for experiment yet to determine, and these little vessels contained every article by which we were to expect to subsist or defend ourselves. However, as the state of mind in which we are, generally gives the coloring to events, when the imagination is suffered to wander into futurity, the picture which now presented itself to me was a most pleasing one.

“Entertaining, as I do, the most confident hope of succeeding in a voyage which had formed a darling project of mine for the last ten years, I could but esteem this moment of my departure as among the most happy of my life.”

|

|

By journey’s end back home in 1806 after enough adventures for several lifetimes, the expedition had recorded nearly 300 kinds of plants and animals that were new to science.

High atop 600-ft Coxcomb Hill, past the dozens of meticulously maintained Victorian homes, is the Astoria Column, celebrating history in an Italian bas relief style known sgraffito which spirals around the 125ft-high tower painted by the Milanese-born immigrant artist, Attilo Posteria. The tower can be climbed but even from its base offers spectacular views.

Five miles south of town, nestled in thick pine woods, is the reconstructed Fort Clatsop in which the 33-strong expedition spent 100 gloomy winter days, only 12 without rain, before beginning their return journey. The fort was a substantial construction with strong gates, probably to keep out bears because the group maintained good relations with the local Indians, one of whom, Chief Joseph, who appears to have been a very enlightened man, quoted by a later visitor as saying that if the white man wanted to live in peace with the Indian, he could live in peace.

“Treat all men alike”, he declared. “Give them a chance to live and grow. All men were made brothers. The earth is the mother of all people, and all people should have equal rights upon it. You might as well expect the rivers to run backward as that any man who was born free should be contented when penned up and denied liberty to go where he pleases.”

|

|

About the explorers, he reminisced: ”The first white men of your people who came to our country were named Lewis and Clark. They brought many things that our people had never seen. They talked straight. These men were very kind”.

Undoubtedly the Indians must have been rewarded with the commemorative silver coins bearing Jefferson’s portrait backed with a message of peace and friendship. In an echo a century later, another coin (the sadly neglected silver dollar) bore the portrait of one of the party, Sacagawea, the teenage Shoshone who was hired along with her 50-year-old French Canadian trapper husband to act as interpreter and guide. The Lewis and Clark Journals make few references to her and only one, dated August 17, 1805, in which her personal emotions are mentioned:

“Clark and Lewis soon after met with the chief… After this the conference was to be opened, and glad of an opportunity of being able to converse more intelligibly, Sacajawea was sent for; she came into the tent, sat down, and was beginning to interpret, when in the person of Cameahwait she recognised her brother: She instantly jumped up, and ran and embraced him, throwing over him her blanket and weeping profusely: The chief was himself moved, though not in the same degree. After some conversation between them she resumed her seat, and attempted to interpret for us, but her new situation seemed to overpower her, and she was frequently interrupted by her tears.”

In what is now the nearby resort town of Seaside, Lewis and Clark set up a subsidiary camp to boil seawater for curing the ten pounds of meat on the daily Fort Clatsop menu. A salt cairn display marks the original site, and recently for the first time since, an Oregon entrepreneur revived and refined the process, making pure salt in a 40-hour process which Ben Jacobsen says took three years to learn.