The Column of Lasting Insignificance: October 4, 2014

by John Wilcock

“I’ve crossed some kind of invisible line. I feel as if I’ve come to a place I never thought I’d have to come to. And I don’t know how I got here. It’s a strange place. It’s a place where a little harmless dreaming and then some sleepy, early-morning talk has led me into considerations of death and annihilation.”

— Raymond Carver, Where I’m Calling From: New and Selected Stories

“I try to stay in a constant state of confusion just because of the expression it leaves on my face.”

— Johnny Depp

“And I can’t be running back and fourth forever between grief and high delight.”

— J.D. Salinger, Franny and Zooey

“Don’t be afraid to be confused. Try to remain permanently confused. Anything is possible. Stay open, forever, so open it hurts, and then open up some more, until the day you die, world without end, amen.”

— George Saunders, The Braindead Megaphone

“During the 1960s, I think, people forgot what emotions were supposed to be. And I don’t think they’ve ever remembered.”

— Andy Warhol

Chapter 11.

Andy Warhol (part 2)

First encounter….People talk about him….

His movies….We go to Rutgers, Ann Arbor …What people say about Andy

EARLY IN MY association with the Factory scene, Andy decided to take the show on the road, having received invitations from Rutgers College Film Society and the college at Ann Arbor. Eleven people, including myself, piled into a rented minibus to make the 1,500-mile round trip, with the blonde singer Nico at the wheel and two separate breakdowns on the Ohio Turnpike. As we dallied in a coffee shop for hamburgers en route, while I sat next to Andy I observed how little talent I had as an artist and how I envied their ability to draw something that was recognizable. Grabbing a paper napkin, Andy proceeded to give me a simple art lesson which I studied but was unable to duplicate with any accuracy. Ah, if only I’d possessed a video camera in those days. And then, in an act of unwitting ignorance, I crumpled up the napkin and threw it away.

We arrived at Rutgers to find the campus a hive of apathy: a mere 200 of the 1,000 available seats had been sold and most of the posters advertising the event had been torn down by ill-wishers. That was all that was needed to goad Barbara Rubin into action. The 20-year-old filmmaker who had introduced us all to the Velvet Underground one night in a Greenwich Village cafe had a unique method of filming which consisted of jumping up and down with her camera more or less in synch with whatever moving objects she happened to be filming and if her subjects tended to be motionless when she arrived, her provocative style soon got them, if not hopping mad, at least hopping.

Accompanied by a slender, golden-haired girl named Susan whose beauty, hair-trigger mind and appealing simplicity invariably reduced strong men to jelly she set off for the cafeteria where, after helping herself to tidbits from diners’ plates, soon found herself surrounded by a score of admiring, questioning college boys.

Sniping away with his camera all the while, Nat Finkelstein—a photographer who had arrived at the Factory to do a magazine feature the previous year and had hung around ever since—soon got into a raucous argument with the officious cafeteria manager who threw us all out.

It didn’t take long for word of the cafeteria contretemps to get around and the first show that night was packed although, as always, it took some time for the audience to decide whether they were being conned or not. Usually what helped this decision was the magic moment when they decided that as the technical quality of the films was so atrocious—compared to what they had become used to—there must be more going on than met the eye. What they then had to decide was whether the atrociousness was intentional or not, a conclusion that Warhol audiences could rarely be certain about.

|

|

By the time the second show was due to begin, Barbara Rubin had discovered that the screen was retractable so the movies could be screened on a constantly shifting background. “Fantastic!” said Andy as she flickered colored gels in front of the main projector. Three other projectors were operating simultaneously from different parts of the hall. There were movies on movies on top of people who were appearing in movies…Nico’s face, Nico’s mouth, Nico sideways, backwards, superimposed on the walls, on the ceiling, on Nico herself as she stood impassively on stage singing.

Dancing onstage with Ingrid Superstar was Gerard, blond locks falling across his face as his head rose and fell with the jerky movements. Two foot-long flashlights in his hands probed and stabbed randomly at the audience. Susan, the golden girl, and a tall student were fighting a duel in the aisles with movie cameras, turning away from each other and then rushing back both cameras blazing furiously.

Upfront, a man stood up ostentatiously, pushed his way past all the people in his row and slinging his coat defiantly over his shoulder walked to the exit door and slammed it loudly behind him. At the back a girl was leaving, too, but as I unobtrusively followed I saw her walk onto the campus, toss off her shoes and do a little dance on the grass beneath the trees. Her red dress shimmered in the moonlight.

I smoked a joint and went back in to see Andy, in black suede suit, his right hand rhythmically tapping his rear pocket, seize one of the projectors and sweep a beam of light across the US flag beside the stage. Some of the audience was getting hostile. “Speak English—if you can ” heckled a gruff voice as Nico announced a number in her slightly guttural tones.

After the briefest of intermissions, the Velvet Underground went on, their most notable attribute (I wrote at the time) “a repetitive, howling lamentation which conjures up images of a schooner breaking up on the rocks. Their sound, punctuated with whatever screeches, whines, whistles and wails can be coaxed out of the amplifier envelopes the audience with disploding decibels, a sound two and a half times as loud as anybody thought they could stand”.

(Explaining their association with Warhol some time later, Lou Reed told me; “Well, obviously he loved the music. We were doing what he was doing except we were using music and he was doing it with lights. But people don’t understand him, they think he’s strange, he’s this or that. They don’t understand that they’re talking about a very, very good person. A very honest person who’s enormously talented”.)

Before the show was over, the fire alarm went off, a monotonous bell tone synchronized with the winking of a red ceiling light. “It’s all the smoke, happens all the time” said a student calmly. But the English professor who had staged the show was skeptical. “Some of the kids found out how easy it is to hold a match near the alarm” he explained. “They do it all the time when they want to be disruptive”.

|

|

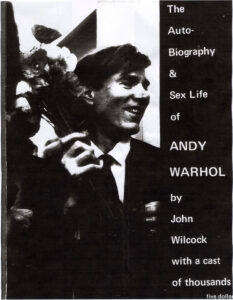

“Warhol studies can plausibly be said to have begun in 1970, the year in which the first two scholarly monographs devoted to his work-Rainer Crone’s Andy Warhol and John Coplans’s widely distributed catalogue of the same name–were published. Although both represent serious attempts to provide art historical analyses, in retrospect it seems to have been John Wilcock’s unassuming, slightly irreverent, and virtually self-published The Autobiography and Sex Life of Andy Warhol (1971) that succeeded in setting the tone for a majority of subsequent Warhol literature.

“The method Wilcock pioneered in assembling a collection of interviews and statements by the artist’s associates and superstars has become a staple within the field. The work of Patrick Smlth, Lynne Tillman, and most recently (although less successfully) John O’Connor and Benjamin Liu are all reminiscent of its structure.’ Indeed, many of the book-length personal memoirs and biographical recollections of life at the Factory can be seen as larger entries within the same category.

“Wilcock’s title promises a revelation of Warhol’s true character, a claim that, on reading, reveals itself as false sensationalism, the unfulfilled promise of consumer desire. Yet, by weaving his book around this premise, Wilcock cleverly engaged with Warhol’s self-fashioned image, reinforcing the impression that Warhol had nothing to say on his own behalf, that there was, behind the surface, nothing there. In the place where an interview with the artist might have appeared, Wilcock cleverly inserted an image of Warhol (appropriated from the cover of Coplans’s book) and added an empty speech balloon issuing forth from his mouth”.

—Branden W. Joseph, Review: One-Dimensional Man, Art Journal, Vol. 57, No. 4. (Winter, 1998)

AT THE FACTORY there was filming every day, or almost every day, and I tried to be there as often as possible. I was usually the only one holding—though goodness only knows what kind of stimulants the more outré cast members were on—and ever willing to share the joint with whoever asked. There seemed to be a general perception in the outside world that drugs were always part of the scene but as I didn’t indulge in anything stronger than the weed I was never conscious of it. In any case, hard drugs were never in evidence and I suspect that uppers and downers were about the extent of it. I dimly remember that when I passed a joint to Andy one day that he took a drag but I can’t say for certain. I may just have imagined it.

In any case, I didn’t do so again although most people there were happy to partake. Edie Sedgwick was always grabbing the joint from my hand and, for that matter, seemed to give her best performances when stoned although ‘performing’ may not be the correct word for the Poor Little Rich Girl she portrayed while reading, smoking, chatting on the phone, making coffee, lounging on her bed and—the first time Andy moved the camera—leaping up to go to the refrigerator.

Apart from commercial successes such as The Chelsea Girls and Lonesome Cowboy, most of the movies were shown once and then stockpiled away in Andy’s house and one day I asked Gerard what he planned to do with them. “He’s got an ego predicament to solve”, Gerard said. “He knows they’re of value and he knows they’re in demand and that’s why he’s holding them back. Although he’s basically a voyeur and wants everybody to expose themselves completely, he won’t expose himself. He likes to keep a lot of mystery. If he didn’t have all those films, then there wouldn’t be anything to hide.”

In the opinion of Charles Henri Ford, who first met him at his sister’s party in 1962, Andy had always been financially secure. “That’s one reason why Andy is where he is; if he’d been a poor, starving artist I don’t think he would have gotten anywhere. It’s really investing in himself that’s got him where he is today.”

“He brought shamelessness into the artist going commercial or in columns or fashion magazines; he took away the stigma of artists not doing anything for publicity or for commercial reasons.

“You get what you ask for. Picasso was an integrator of all styles, the greatest artist of his time because he could integrate everybody’s style including 16th, 17th century, ancient Greek and God knows what. He turned everything into Picasso which doesn’t mean he invented all those things but they came to him. They already existed and he transforms them by his own alchemy, his own magician-ship, into Picasso. Well, Andy has done more or less the same thing. Andy living on a desert island wouldn’t be Andy.”

I suggested that the atmosphere around him was almost like a school because although he learnt a lot from other people they also learned a lot from him. He appeared as such a strong character that people tended to emulate his way of handling things.

“Yes,” Charles agreed, “because of his flair for picking out things that are in the air, which are bound to congeal in the future. Andy is a combination of flair, luck and publicity. Without one of those elements he wouldn’t exist”.

A longtime Warhol friend, Sam Green, offered a similar viewpoint. “As conscious as he is about style, and all those visual things, I really don’t think he thinks of his life as a work of art”, Sam explained. “I know he thinks ahead, a long-term plan. I think he’s always had an all-encompassing desire to be well-known, to be conspicuous. A lot of people have that, all of the people around him, that’s what they’re doing it for. They don’t want peace, they don’t want security, they don’t want money, they don’t want possessions. All they want is when they walk down the street is for people to turn around and say, ‘Oh Gosh, I saw her picture in Life last week’ I mean, who cares? But they’re driven by that sort of thing.”

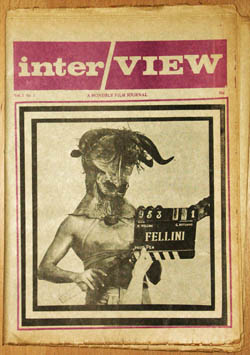

Various members of the Warhol entourage have offered reasons over the years for the genesis of Interview. Gerard Malanga, for example, has told interviewers it was because they wanted to go to parties. But of course the Factory already had more party invitations than it could handle. On one occasion, as a matter of fact, I collected a sheaf of invitations that Andy agreed he wouldn’t be accepting and went to the parties myself, allowing me to devote one of my monthly High Times columns to “The Parties Andy Warhol Didn’t Go To“.

The way Interview began was with one of the occasional phone calls Andy made to me in which he—once again—was bitching about how Hollywood wouldn’t give him a million dollars to go out there and make a movie. Off-handedly I said, “Well Andy, all my friends publish newspapers; why don’t you produce a paper?” It was met with a noncommittal grunt, but ten minutes later Andy called again. “What kind of a paper?” he asked in that querulous, uncertain voice.

I remember telling him that a film paper would be an obvious choice and offering to put up the typesetting (via my wife’s Ambertype, which was already providing the typesetting for many of Manhattan’s underground papers). Typesetting and printing bills would be about equal, I said, and thus we could share ownership of the paper. At the time I was busy producing Other Scenes, a semi-radical tabloid I had begun a year or two previously, and as my travel writing job was still necessitating regular trips to Japan and Greece I was too busy to even think of getting involved editorially.

|

|

But I did suggest that he follow the example of Art D’Lugoff’s Village Gate and call the paper Andy Warhol’s inter/VIEW (he had come up with that title). No, he replied, he didn’t want his name on it, nor did he want it printed in color. What style would the paper follow? I asked, figuring that anything Andy came up with would be imaginatively innovative. “I want it to look like Rolling Stone “, he said determinedly, to my surprise.

And thus Interview was born and Andy began to carry a tape recorder with him everywhere he went.

But I was getting increasingly unhappy with New York and about a year later, before I packed up and left for Europe, I told Andy that I’d like to sell out my share of Interview, while retaining a small percentage in case it was ever successful. Some years earlier, after being a cofounder of The Village Voice, for which I had written a weekly column for 10 years, I had left with nothing and I didn’t care for the experience to be repeated.

But Andy was adamant that it had to be all or nothing (as usual with Andy’s business dealings, there was nothing on paper) and asked me to give him a bill for the year’s typesetting. I assessed this at cost, a meager $6,000. When it came time to leave and he still owed me $1,000 I asked him to settle up with me by giving me one of his pictures. He signed over to me a couple of the big flower paintings that had just returned from being exhibited at the Tate Gallery. At the time any dealer would have valued them at $500 apiece because they were on paper, not on canvas, which would have doubled their value. As I was just about to leave the country, I traded them to my dealer for a substantial amount of smoke.

Interview, subsequently edited by a man I always thought of as ‘Bob the Snob’, went on to become a great success, largely due to the Snob’s sycophantic worship of the rich and socially connected which increasingly became Andy’s chosen milieu. I never did read the magazine again and only saw Andy rarely afterwards.

|

Diary — Sunday: So many of the contributors to any publication want you to print their poetry, but being a hard-headed newspaperman— just give me the facts, m’am—I never have space for such indulgence. Let’s face it, most poetry is rubbish—a bunch of words presented in a highly-stylized form that, if rearranged and presented as prose, would cause their author to be laughed out of the room. Obviously a high percentage of prose is also rubbish but most of it is not passed off as something special and therefore entitled to special consideration, even reverence. …..”Do not retell in mediocre verse”, advised Ezra Pound, “what has already been done in good prose”. Good poets, however, are something else. What they write is evocative, often imaginative, sometimes inspiring although the irony is that good poets don’t actually need to write at all, for their view of the world and their attitude towards life benefits us all. Like good artists with whom they have synchronicity. My meeting with Marilyn Monroe left me with one meaningful quote I have remembered ever since. “I like men who are poets” she said. But that doesn’t mean they have to write poetry. D’you know what I mean?” Indeed I do. |

Bakewell (part 2), its mayor, and its pudding…

National Weed (1974, issue #3)

it’s here…