The Column of Lasting Insignificance: September 11, 2010

John Wilcock

Luckenbach, Texas

The romance of this place was in my mind as soon as I heard Waylon Jennings singing the eponymous song, and my plans to visit have endured ever since. It’s hardly a place at all, being merely a collection of ramshackle, wooden shanties clustered around a post office (1849) which now serves as a general store offering everything from T-shirts for lady bikers and Stetson hats to guitar-shaped flyswatters.

Luckenbach, Texas: photo credit unknown

Framed by a group of 500-year-old oak trees, the biggest building is the dimly-lit dance hall, booked for much of the year by weddings and other celebrations in addition to the Friday night dances and other shindigs. There is music seven days a week, with Jimmy Lee Jones on site much of the time. (You can see him render Luckenbach, Texas, on the Wait A Minute show on this website and buy his CDs in the store).

It was an eccentric local rancher/philosopher named Hondo Crouch who paid $30,000 for the abandoned, century-old German ghost town back in 1970 (he died in 1976) but Willie Nelson and Waylon more or less adopted the place and still turn up at least once a year for the annual summer picnic. Founded almost a century earlier by an itinerant German preacher, his daughter named Luckenbach after her fiancé.

“Everybody’s Somebody in Luckenbach,” goes the community’s slogan and there’s nary a visitor who doesn’t feel blessed to be there.

My quick trip to Texas was to visit Austin where I met my new friend, cartoonist Ethan Persoff with whom I hope to collaborate on a book. The 2,700 miles I covered round-trip inevitably resulted in a traffic ticket in Texas which seems to have devised its near-perfect highways and 80mph speed limits to encourage speeding, while simultaneously stationing traffic cops unobtrusively at intervals frequent enough to catch a constant stream of speeders.

Only a 5% margin is allowable so if you get caught going 84 it’s an immediate $140 fine and on divided highways, with cars as much as a mile or so apart, it’s the easiest thing in the world to exceed the limit, an income that Texas has surely come to rely on. It seems safe to assume that with four cars lying in wait at different points on the 70-mile stretch between Marfa and I-10 alone, that $1,400 a day or almost $10,000 per week would be levied. And can we guess that, considering the size of Texas, this might be multiplied by 100? (that would mean an income from speeding tickets alone of $1million per week. Nice going).

My visit to famous Marfa was to see the works of Donald Judd and those of his Chinati Foundation, but being Sunday everything was closed up tight so I was lucky to at least find the gallery of Mary Etherington open. A former New Yorker, Mary said that though Marfa was quiet and isolated she met there visitors from all over the world. But when I asked what advice she had for artists who aspired to come and settle in this famous artistic community, she laughed and replied: “Don’t.”

The 1956 filming of Giant, directed by George Stevens, was filmed in Marfa, its stars — James Dean, Elizabeth Taylor, Rock Hudson, and Dennis Hopper — staying at the charming, Spanish-style Paisano Hotel where you can still watch a DVD of Giant on a monitor in the lobby. More recently here was the filming of the Coen Brothers’ No Country for Old Men.

Just west of Marfa is a viewing site at which visitors can watch for the notorious Marfa Lights, mysterious spheres which hover in the night air unpredictably ten or twenty times a year. Supposedly they have been observed for at least a century, at first attributed to Indian campfires (or, by the Indians, spiritual signs) and later to swamp gas, distant car lights, or a mirage. The mystery of the lights’ origin has never been solved but Wikipedia says “the dominant skeptical explanation seems to be that the lights are a sort of mirage caused by sharp temperature gradients between cold and warm layers of air.”

Most of my driving time I listened to the radio, once hearing a waitress taking orders from truckers and assuring them their food would be ready when they arrived. But the tone of the talk shows was predominantly angry, ranging from contentious to paranoiac. Most reflected a deep-seated suspicion about what they presumed to be the Muslim agenda, a well-thought-out campaign to introduce sharia law to the country. “That’s obviously the basis of their faith,” one said, “so why wouldn’t they do anything they can to promote it? They’re patient and know that the rage over 9/11 will fade away. They just have to wait and make their gains incrementally.” And the reason why moderate Muslims don’t speak up? “Because they’re well aware of what happens to unbelievers,” the caller said ominously.

Several Western states have devised another way of reaping income from unwary traffic: every now and then a sign will indicate that the next few miles are a “traffic emergency zone in which traffic fines will be doubled.” Sometimes road work is going on, or one lane of the road marked closed, but quite often the section is no different from the previous part of the highway.

A few miles before Flagstaff it’s worth taking a short, nine-mile diversion to the Meteor Crater, the spot where a meteor plunged into the ground at an estimated 26,000 mph, carving a hole hundreds of feet deep and a mile across. At the beginning of the last century, a Philadelphia mining engineer took the lease on much of the land before spending 26 years digging for the ‘lost’ meteor before deciding that it must have vaporized.

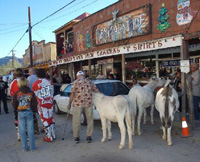

Oatman, Arizona

THE OLD GHOST TOWN of Oatman on Route 66 has an official population of 128 but gets half a million visitors every year to crowd the sagging, wooden sidewalks, buy souvenirs, and admire the sometimes-snappy burros that meander across the main (only) street. The feisty beasts are descendants of those that accompanied the gold prospectors early in the last century and there still is an active goldmine just outside of town but output is far below the millions of dollars worth mined in the early days. Oatman is a late-rising place and at my 10am arrival, even the burros were apparently still asleep and many places were still closed. These included the famously decrepit Oatman Hotel where Clark Gable and Carole Lombard spent their honeymoon night in 1939. For a small extra charge you can stay in the same room but it’s a bit primitive with no toilet or running water, although legend fills the air like a cloud.