The Column of Lasting Insignificance: September 13, 2014

by John Wilcock

“And when suddenly

the god stopped her and, with anguish in his cry,

uttered the words: ‘He has turned round’ –

she comprehended nothing and said softly: ‘Who?’”

— Rainer Maria Rilke

“I don’t quite know yet,” Alice said very gently, “I should like to look all round me first, if I might.”

“You may look in front of you, and on both sides, if you like,” said the Sheep; “but you can’t look all round you — unless you’ve got eyes at the back of your head.”

— Alice talking with the Sheep from Alice in Wonderland

From my Autobiography Manhattan Memories

Chapter 02. Meeting Marlene

Greenwich Village, 1955

Gilbert Seldes’ The Lively Arts

Birth of the Village Voice

Aggravation by Norman Mailer

Giving Parties to meet strangers

Marlene Dietrich: glamorous grandmother

SELF-AWARENESS has never been my strong suit. The simple act of sitting down and quietly examining who I was and where I was heading, was not something that even entered my mind until I was much older. In those early days in Greenwich Village I was too much in love with my new home to have time for any diversion. To this young immigrant writer, New York was exciting. It seemed to have everything: a variety of attractions from theater, opera, ballet, museums, ice hockey, enticing bars and great restaurants, that people invariably listed as their reasons for not being able to leave (even if they never went to any of them).

As it seemed to me then, this volatile city was indeed one of rosy allure. It seemed to embody all the clichés with which the songwriters had endowed it: gleaming spires, teeming hordes, sweeping avenues of adventure. It was a joy to walk around the Village’s beguilingly peaceful streets, all bathed in what now seems to have been a perpetual springtime. Muggers? A term, maybe even a concept, not yet invented. Money? Hardly seemed important even if one didn’t have much. Things were cheap. Life was promising. I was still friendless but with so many things to do I didn’t devote much time to thinking about it.

I’m fully aware of how our memories always enhance and subtly polish what might have been not quite such a radiant reality but honestly, thinking back now, all I can remember is how happy I was in this big, all-too-accessible city. I’ll take Manhattan. Indeed.

In the years to come, I now realize, my professional preoccupations became directed much more to the future than the present. What were the implications of this? What was going to happen next? It’s still something that guides my thinking whenever I write about some new trend or document, some apparent prediction. But in those early days of my new life I was really living for the moment. “Each day… a little life” wrote Schopenhauer.

Knowing virtually nobody, I spent my first few weeks in tiny Greenwich Village bars basking in the enticing allure of sentimental Frank Sinatra records on the jukebox and speaking to no one. It was only when I rented a street-level apartment on Waverly Place and hung my hammock from the railings, that I made my first new acquaintances from among the curious passers-by. There’s nothing like reclining in a hammock to provoke envious or admiring comments, especially when the hammock adjoins a busy sidewalk.

And now I had my first job, working as an assistant editor on the pocket-sized Pageant magazine whose editor, Harris Shevelson, was a zealot about participatory journalism. One of his ideas was to zero in on a Waverly Place apartment building and introduce readers to the lives of people who lived here. Next he bought a crate of whisky and invited the staff to drink it all, subject to being timed and tested every hour on how ineffectual we had become at performing various tasks as we got progressively drunker. One of my assignments was to obtain all the racing papers for the previous week and laboriously match the results against what forecasts had been made by a handful of tipsters beforehand.

In magazine terms I was still wet behind the ears but I learned a lot from Harris Shevelson. One of his unusual ideas was to discourage selling subscriptions to Pageant on the grounds that newsstand sales would tell him what he most wanted to know: were more copies sold this month than last? And, if so, what might be the reason? Like most magazines we had to construct three or four cover lines for each issue: one always had to contain the word sex.

THE VILLAGE seemed so peaceful in those days, still basking in the memories of the artists, publications and literati who had spread its name around the world. Delmore Schwartz edited the Partisan Review on Astor Place, Eugene O’Neill had overseen productions of his plays at the Provincetown Players on MacDougal Street and a host of famous writers had met, lived or worked in nearby Washington Square: Edith Wharton, Sherwood Anderson, Scott Fitzgerald, Robert Louis Stevenson, Sinclair Lewis, Willa Cather, Mark Twain, H.L. Mencken, Hart Crane. Henry James had written a novel bearing its name and a plaque on the square’s north side marked where he had lived.

Chumley’s, the unmarked bar on Bedford Street, became one my favorite spots, its walls carrying the framed covers by novelists who had preceded me: John Dos Passos, Edna St Vincent Millay, Theodore Dreiser and others whose names were yet unknown to me. I used to wonder wistfully if one day something of mine might be among them.

I hadn’t read all these authors but I’d heard of them and was aware that the Village’s reputation for publishing avant garde papers and magazines went back for well over a century. I searched for some mid-20th century equivalent but found nothing except an existing paper, the Villager, which carried news of local tea parties and an insipid column ostensibly written by the editor’s cat named Scoopy Mews, a piece of camp that was a decade or two before its time.

Climbing the steps to a jewelry store on 8th Street, I went in to ask its bearded owner Sam Kramer: “Why doesn’t this famous bohemian Greenwich Village have a proper newspaper?”

“Why don’t you start one?” was Sam’s rejoinder, and within a week of my arrival I had pinned up a notice in a Sheridan Square bookstore asking for volunteers. Through that I met Ed Fancher and Dan Wolf, both then working at the New School but not quite as penniless as myself. More than a year was to pass, however, before we met again at which point Fancher decided to cash in his telephone stock and finance a weekly paper, assisted by Dan, then a press aide at the Turkish Information office; Jerry Tallmer, an editor at The Nation and myself.

I remember Dan telling me that his boss used to subscribe to a clipping service about Turkey but got so flooded with irrelevant clips around Thanksgiving that they declined to renew. It was the only joke I ever heard him tell. Dan’s girlfriend Rhoda had gone to school with Norman Mailer whose The Naked and the Dead, a treatise about his Korean War experiences had recently become a best seller (“Write us a good antiwar novel, man”–“Well, just a minute until I shoot another gook man, then I’ll sign up” was how Kenneth Rexroth sardonically described that event). My cynical observation was that famous authors who were paid by the word had a tendency to be a bit windy.

Mailer, who came up with the paper’s name after we’d all filled reams of paper with less desirable suggestions, decided to write a weekly column, the first of which began:

“Many years ago I remember reading a piece by Ernest Hemingway and thinking, ‘What windy writing…” The column was basically an apologia for its own existence but went on to suggest that novelists were “more columnistic than the columnists. Most of us novelists who are any good are invariably half-educated; inaccurate, albeit brilliant on occasion; insufferably vain, of course; and, the indispensable requirement for a good newspaperman, as eager to tell a lie as the truth”.

The second week doubled his Wind Quotient:

Quickly, a column for slow readers lapped over the two full columns into an adjoining single column and concluded on a six-inch turn further back in the paper. Devoted to the subject of communication, it predated McLuhan in containing a real truth that nevertheless was virtually unintelligible, concluding with:

“Therefore brethren, let me close this sermon by asking the grace for us to be aware, if only once in a while, that beyond the mechanical communication of all society’s obvious and subtle networks there remains the sense of life, the sense of creative spirit…and therefore the sense no matter how dimly felt of some expanding and not necessarily ignoble human growth”.

This pretentious and condescending rubbish was not being sympathetically received by Voice readers, some resorting in response to parody, but most accusing the star columnist of pomposity, verbosity, half-baked opinions, being patronizing and suffering from “illusions of grandeur”. Understandably, however, the publicity brought welcome attention to the paper, and this was magnified when Mailer chose to devote a half page ad reprinting all the crappy reviews that had appeared deriding his third novel, The Deer Park.

In the course of time, however, this book did get some good reviews. Writing almost thirty years later, Mary V Dearborn judged that although “its philosophical claims are meager, (it) is a highly enjoyable and provocative book, the writing stylistically Mailer’s strongest”. The Deer Park sold more than 50,000 copies and rose to sixth place on the New York Times’ best seller list.

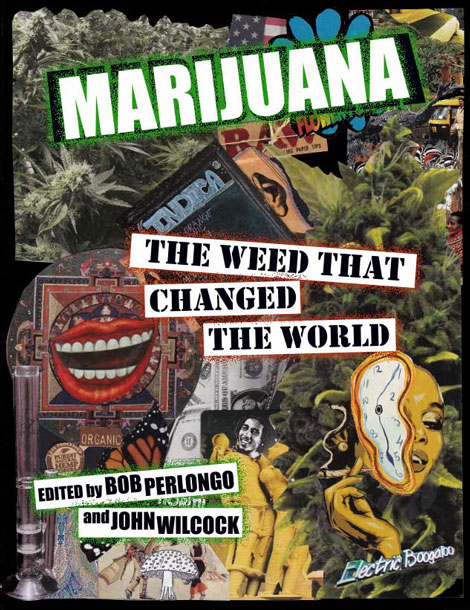

In his sort-of autobiography, Advertisements for Myself (1959) which pointedly omitted me, and only me, from his list of Voice staffers, Mailer confessed that the book had stemmed from his adoption of marihuana which had led to a revolution in his thinking. “I felt that I was an outlaw, a psychic outlaw, and liked it, liked it a good night better than trying to be a gentleman”.

IN MY EARLIER LIFE in Canada, I had attended a lecture by Gilbert Seldes, known to me only at the time as somebody hired by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation to give an introduction to this new medium, television, on which CBC had just embarked. Now, a year or two later, I read about his reputation as a culture critic and author of a best seller, The Lively Arts, and urged Jerry Tallmer to accompany me and invite him to contribute a column to the Voice. Our tentative suggestion that he might write for us ”occasionally” was met with a vehement: “No I will not. I will only write for you if I can write regularly.” Thus, we acquired our second star columnist, a gracious contrast to Mailer.

But, even as the paper’s circulation began to pick up, Ed and Dan realized that it was not fast enough to survive financially without outside help. Tallmer and myself were working 16-hour days for $25 per week, and with all the other expenses, Fancher’s original $14,000 soon ran out and after a series of fierce rows, Mailer and a young loafer-about-town named Howie Bennett agreed to refinance the paper.

Their conditions were that if Fancher and Wolf couldn’t make a go of it within a year, they would take over and run the paper. Before that 12 months was over though, Mailer had, to all intents and purposes, bailed out. He offered me a joint once, but in those days I was too dumb to know the difference between marihuana and other drugs (as many people still are even today) and nervously turned it down.

The Voice deserved to be noticed if only for sponsoring such pioneering concerts as those of electronic musician Edgar Varese and the by-then almost-forgotten Billy Holliday. And the fledgling Off-Broadway movement, which did so much to boost little theatres, only became so through the efforts of Tallmer, our drama critic. But there was just no money coming in and Fancher’s stake plus the input from Bennett and Mailer was soon exhausted.

UPTOWN, i.e. ANYTHING NORTH of 14th Street, was anathema to me in those days, but occasionally I’d venture into midtown streets invariably pausing for a few words with the blind poet/composer Louis Hardin, known to most people as Moondog and an even more familiar a figure than most politicians. Bizarrely dressed in an abundant felt robe with a twin-pointed Viking-style hat, he would stand motionless on a corner in the West 50s for hours, holding upright a six-foot spear, soliciting–but never asking–for money, by offering for sale his poems (“Be a hobo and go with me, to Hoboken by the sea”) or playing a rhythmic number on his drums. “I have to make my overhead” he would say, always keeping his remarks to a minimum and displaying almost no curiosity about his interrogator.

“I came here to seek fame and fortune” he once remarked, “and so far I’ve achieved fame”. Leonard Bernstein, Marlon Brando, Julie Andrews and Charlie Parker have all claimed to be among his friends and many years later, Atlantic Records released an album of his music, Sax Pax for a Sax in 1997 when he was reported to be living, aged 81. in Germany’s Ruhr Valley.

BY THIS TIME I had made a few friends in New York, often by striking up conversations in the subway (it was a more innocent time) or in the bars. Invited to a party in a Bleecker Street loft, I asked Bud Waldo, the host, if he’d like to “share” another party some day, explaining that we each invited a few friends and stumped up $10 apiece (it was a much cheaper time) for a barrel of beer and paper cups. After Bud agreed we pulled off several successful gatherings with my guests usually the result of handing out stamped cards:

Next party on…..…..At………

BYOB

on which I had filled in the relevant blanks with date and address. The parties were terrific largely because I circulated constantly introducing people I didn’t know to other people I didn’t know. Amazingly enough, this strange mix of writers, plumbers, artists, tourists and what-have-you mingled so well that I was constantly being complimented, even years later, by strangers who said they had rarely attended such heterogenous gatherings. And, of course, it’s true that most of the parties we attend are with people of “our own kind”, whatever that may be. Judy Collins, Woody Allen, Orson Bean, Sally Kirkland, Mary Travers and Hugh Hefner’s brother Keith were among our early guests and Jeff Blyth, a former newspaper colleague of mine from Newcastle-on-Tyne, went off and married an old girl friend, Myrna, after I introduced them. She reached the editorial heights in the women’s magazine field but apart from a casual meeting at a party years later, never spoke to me again. I was often being told of similar Cupidic match-ups for which I’d been responsible.

What first got the Voice moving was an attack by Steve Allen on Hearst columnist Jack O’Brian, a bigoted television critic who had been sniping away in his Journal American column at Allen’s “pinko” sympathies. Allen was sympathetic to the Voice having displayed on his program the first issue on his show (October 26, 1955). Now Steve wanted us to run his fiery reply to O’Brian’s allegations and we were delighted to do so.

The article created a minor sensation on Madison Avenue. Television performers just weren’t in the habit of replying to critics, particularly powerful reactionary ones still trading on the McCarthy-ite accusations of communism. Everybody in the industry rushed out to buy this hitherto obscure Greenwich Village weekly.

Despite this small blip in its fortunes, the Village Voice was still growing much too slowly. A couple of years after its inception and priced at a nickel, it was being bought by less than 5,000 people. In these days when every community and every faction has its own tabloid papers it’s perhaps hard to visualize the day when, apart from the Voice , there were only the “straight” papers, meaning conventional dailies (in addition to the Times and Daily News, New York had half a dozen others) plus a few conventional weekly papers.

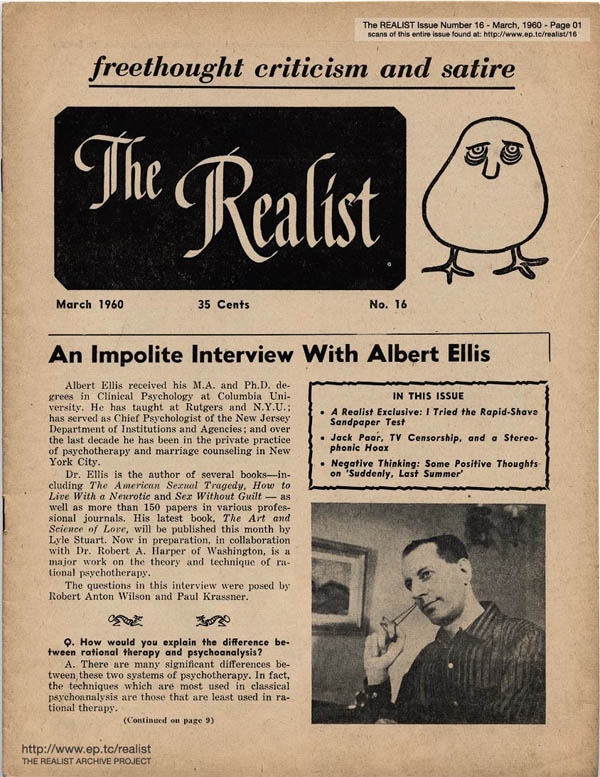

WHEN I HAD FIRST arrived in New York the best-known maverick publication seemed to be Dorothy Day’s The Catholic Worker which a wild Irishman named Ammon Hennacy used to sell for one cent on street corners. (Accused one day of being a communist he said, “I’m worse than that , madame; I’m an anarchist”). The bearded poet (and later Fug) Tuli Kupferberg began self-publishing tiny booklets one of which, 1001 Ways to Live Without Working (“the most stolen book at the Paperback Gallery” ) sold 5,000 copies, and Paul Krassner eventually left Lyle Stuart’s Independent to create The Realist which became the bible of every independent thinker.

Another of Tuli’s books was…

100 Things to Do After the Revolution

9. Meditate

13. Teach something someone wants to know

21. Plant beans

22. Go live in the desert and meditate

30. Walk across England

31. Bicycle thru Germany

32. Call up your mother

47. Pet a dog or (cat)

55. Visit the moon

68. Laugh

72. Get lost in a strange city

77. Sit In a tree

83. Touch her toes

100. Talk to yourself.

Paul told me that he and Lyle had been discussing the split that had developed in the organization behind a free thought magazine, Progressive World, and Lyle proposed to the publishers–an elderly couple from whom the publication was, in effect, being stolen–that a lively new free thought magazine should be published, and that it could be launched with their mailing list.

“With you as the editor”, Lyle added. “You’ll be perfect; the only person I know who’s neurotic enough to do it.”

Neurotic or not Paul produced a free thought magazine for the new age (I’ll get to one of my heroes, Julius Haldeman in a later chapter). The Realist cast a skeptical, cynical eye on all the things that True Believers—the kind who would be Bushites today—held dear, but always with a kind of playful undercurrent. Naturally, one of his early subjects was Albert Ellis, the maverick psychologist who had become a monthly columnist for the Independent, columns collected and published as a book, Sex Without Guilt.

“I wrote a parody for Mad magazine called Guilt Without Sex–a sex manual for adolescents” Paul told me, ” but it was rejected because of its subject matter. I sold it to Playboy instead”.

My own involvement with Ellis, who died in 2007, had come about reading his books and learning how much he had offended the psychology establishment by his confrontational approach to his patients. “Why can’t you accept that some people are crazy and violent and do all sorts of terrible things?” he would berate them. “Until you accept it, you’re going to be angry, angry, angry. Success is contingent upon forgetting your god-awful past. Stop complaining and deal with it”.

He wrote his first book about love, sex and marriage after his friends consulted him for advice which prompted him to take took a course in psychology at Columbia. When he started his practice, he quickly became known for his sexual liberalism and soon his methods had a name: Rational Emotive Therapy whose principles he laid down in How to Live with a Neurotic. His weekly workshops on 65th St were soon being attended by classes of up to 150 people. “I’m curing every screwball in New York, one at a time”, he observed.

Not long after I met him I was screening possible candidates to assist me in writing a new travel book and listening to the travails of one of them, Janet, struck a chord. “I know exactly who you should meet” I told her. “He’s an offbeat shrink named Albert Ellis and he could respond to all those doubts that you’ve just told me about”.

Janet took my advice, visited Albert, straightened out her head, took a psychology degree and ended up running his Institute for the next 30 years.

IN THE LATE FIFTIES, Ed Sanders (another of The Fugs) already admired for his anti-nuclear escapades, started Fuck You, a mimeographed magazine which carried such contemporary poets as Leroi Jones, W.H. Auden, Michael McClure, Allen Ginsberg. For a long time, the Voice called it F*** You, because the unexpurgated word never appeared in print in those days. Mailer’s novels were peppered with “fug” prompting Tallulah Bankhead’s famous greeting, “Oh, you’re the young man who doesn’t know how to spell ‘fuck'”. Nevertheless, Dan Wolf banned the word from the Voice and chided me for “always writing about your friends”. I replied they’d become my friends after I wrote about them.

Having by this time dabbled my toes in the literary scene, I turned my attention to art, a subject for which Greenwich Village was at least as well known. I didn’t know much about art, nor did I know what I liked but I had a vague knowledge that John Sloan and “the Ashcan Artists” had achieved some renown in earlier years. Now in the early 1950s the predominant mode was abstract expressionism, whose reigning priest was Hans Hoffman. It was a style that held no interest for me, nor was I capable of appreciating it, although the idea of hanging out with artists held a romantic appeal. I spent minimal time in that off-duty artists’ HQ, the Cedar Tavern, but made no contacts and on the solitary occasion I was taken by Voice photographer Fred McDarrah to the “Club” on Astor Place found most of the scintillating conversation to be about Provincetown real estate.

There were regular openings at the West 10th Street galleries but they were desultory affairs with cheap wine and a distinct lack of drama. The glitz was to come a decade later. . I didn’t know much about art, nor did I know what I liked but already I had a vague, undefined sense that the social scene was likely to offer more possibilities than the art itself, a notion that was to be proved in spades in the years ahead.

ANY KIND OF FREELANCE work was welcome to supplement my tiny Voice stipend and luckily Frank Rasky kept me busy with interesting ideas. He called from Toronto to suggest I interview Marlene Dietrich who was dispensing advice on NBC radio, a five minute sound bite of wisdom in her unmistakable gravelly voice. I left a message with her press agent and while awaiting a call back, La Dietrich herself came on the phone and invited me up to her apartment. So with a friend to take shorthand notes, off we went to her modest pad. I remember how tidy it was and how the walls were lined with framed pictures of the men with whose her name has been linked: Jean Gabin, Erich Maria Remarque, Gary Cooper, Michael Wilding, James Stewart, John Wayne. And Ernest Hemingway who Marlene said was the person she turned to for advice. “I pick strong people to take my problems to” she said.

A few years before she had called him “the most fascinating man I know” explaining (in a magazine essay): “He is gentle as real men are gentle; without tenderness a man is uninteresting”.

In her 5-minute segments Marlene sounded confident and reassuring, her advice simple and sound.

- To a woman who complained about having to walk her husband’s dog, her advice was to think of it as “our” dog and not “his” dog. “This would greatly influence your way of arguing and might give much better results”.

- A man of 40 who moaned about being impatient was given a message from Leonardo da Vinci: “Patience serves as a protection against wrongs as clothes do against cold”.

- One man, doubting the value of a mink coat for his wife, was assured that it was not only practical, serviceable and tough–rare qualities in a luxury item–but also an important symbol of emotional security. “How else can your wife state so openly that she is cherished by you, as while basking in the warmth and luxury this badge provides?” Marlene asked.

As we sat comfortably on the sofa in her Park Avenue apartment sipping at drinks, Marlene confided that even in the most miserable letters she could always find “something to guide the writer back to”. It was her belief that people’s attitudes that made them unhappy or gave them with problems. “Most of them are looking inward rather than out. Many people are tempted to run away from their responsibilities and I tell them they are not alone in this”. Today, even at 102 she would probably have been a classic advice aunt.

Marlene, born in 1905 and becoming a star 25 years later with The Blue Angel, was now playing Las Vegas for $30,000 a week. “I adore that town, music plays all night, no door ever closes”.

Yes, she said, she had seen all the references to her as a glamorous grandmother and it “amused” her. People were always asking ‘how do you do it?’ sort of questions but she’d been pleased to find that’s not what people wrote to her about.

“We haven’t had a single letter about makeup and staying lovely” she said emphatically. “It just shows that people aren’t as superficial as we might think. We have nothing about figures, diet, beauty–just nothing”.

Part of her legend, I had read, was that she was never caught off guard. One ladies room attendant said that she’d been watching Dietrich for 20 years and had never seen her renew her make-up.

As I watched her closely I felt that he predominant impression she gave in person was of being glamorous and she must have picked up on it somehow because glamour was her next topic. It was, she believed, within every woman’s power and that being glamorous was a necessary part of every woman’s armor. She shrugged off her annual presence on best-dressed lists as “accidental”.

I read out to her Eva Gabor’s words “She is the real glamour. Marlene stretches her leg, a whole roomful of people jump”.

“If you’re admired”, she said, “there’s a stratosphere you reach where people just aren’t jealous any more. It’s true; women don’t get jealous of me. You should see them in Las Vegas. After a show it’s always the women who crowd backstage to see me. I can see them pushing their husbands along”.

She said she got a lot of questions from women whose children had grown up. “Is my mission in life over?”

“I tell them, ‘A mother’s mission is never over because in the back of their minds her children know she’s there–and that’s her role, to be there. If they’re in trouble they’ll turn to her.’ Much of the time, Marlene said, people couldn’t get back to basics. Even analysis didn’t seem to help. They couldn’t find their way back unless someone shakes them up. “I regard that as my job.”

I knew something of her background: that while working as a film extra in her native Berlin she’d married a young director, Rudolph Sieber, who lived on a California chicken ranch while she stayed in New York. And when columnists linked her with other men she had a standard answer: ” I consider Mr. Sieber the perfect husband and the perfect father. He is a sensible man; no matter what happens to me I can always rely on him. I see him quite a lot each year”, she added. “I make many visits out to the West Coast”.

Their daughter, the TV actress Maria Riva along with her second husband lived a few blocks away from Marlene who had become a proud baby sitter for her grandson. She cooked, too, and was good at it–“the best egg-scrambler the world has ever known” Billy Wilder once said.

But what surprised me was when Ms Dietrich brought up the subject of astrology. It was a subject about which I was something of a naysayer and it must have showed on my face.

“Well, I’m not guided by it”, Marlene said firmly, ” but I believe in it. I can’t accept (the fact) that if the moon has been recognized to pull the waters back and forth like clockwork that I should escape this. Are we stronger than all the water? There’s a lot about it that I don’t know. There has to be. But in the countryside where people work closely with the earth, they can’t do certain things when the moon is waning. To ignore these influences would be stupid”.

Was she a lonely woman, I asked, as people had claimed? “It might be lonely at times but it’s a self-chosen loneliness so I can’t complain about it”.

We had been in the brightly lit apartment for more than an hour and I sensed she had had enough. As we stood in the tiny lobby and Marlene got our coats out of the hall closet, my shorthand-taking assistant spoke for the first time. Did Miss Dietrich mind if she asked a question. La Dietrich smiled at her. “Of course not, dear”.

What advice could she offer to the woman who couldn’t decide a career and marriage, my assistant asked? It was a subject on which she and her boy friend disagreed.

“Unless you have unusual talent” Marlene said emphatically, “I would say, ‘marry, have children and don’t worry about a career. People like you and me, with no extraordinary talent”–(it was astonishing the way she included herself in this statement)–“should marry. I wanted to have a child very much. Without a child a woman is nothing. If you are a scientist or a great artist with a special gift for the world, then perhaps it is possible to sacrifice your own life for your career. But what real thrill does a woman get out of a career that can compare with living for the man she loves?”

She watched us walk to the elevator and slowly closed the door.

First published in 2010 and available on amazon.com and lulu.com

it’s here…